PRP at Home Training

by Christian Sullivan

Few Key Notes:

Training focus if going to shift from throwing and lifting big, to learning how to move well through body weight and stability movements.

Also, we can change stimulus by adding bands/chains and changing the tempo of the movements. Another focus would be mobility. You can make an “at home” workout very dificult by challenging the tempo and/or holding basic movements.

It is important to continue mobility every day to maintain the “gains” that we have worked so hard for. Feel free to mix in the mobility movements into a full body lift for enhanced movement efficiency.

I know some of these movements may be unfamiliar, but they can be found on YouTube. If you have any questions regarding working, mobility, nutrition, the mental side of things, or further explanation on a movement, feel free to reach out to me via email or text.

Body Weight Workouts:

Full Body 1:

4x10 Body Weight Squats

4x10 Pushups (5 second hold at bottom, 5 second squeeze at top)

4x10 Body Weight Split Stance Squats (5 second eccentric (lower))

4x10 Ice Skaters

4x10 V-ups

Full Body 2:

4x5ea Lunge Series (forward, Lateral, Reverse)

4x10 Bear Crawls (Box if able, Lateral, or forward Backwards)

4x10 Tuck Jumps

4x5 Plyo Push-ups (push off the ground, reset each rep)

4x20 Standing Calf Raises (5 second eccentric)

Banded Workouts:

Full Body 1:

4x10 Banded Squats

4x10 Banded Push-ups

4x10 Banded Rows

4x10 Banded Curls

4x10 Banded Tricep Pushdowns (put in door)

Full body 2:

4x10 Banded Chest Press

4x10 Banded Straight Arm Pulldowns (put band in door)

4x10 Banded Hammer Curls

4x10 Overhead Tricep Extensions

4x10 Banded Lunges (rev or forward)

Lower Body (no equipment):

A1 3x8ea BW Reverse Lunge with 3 second hold

A23x5 BW Squat Jump with stick

B1 3x8ea BW Cossack Squat with 3 second hold

B2 3x60sec Moving Plank (Push-Up to Elbows)

C1 3x40sec (ea) Side Plank with Top Leg Lift Offs

C2 3x10 Superman (3 sec Hold)

D1 3x3ea 4-way Single Leg Squat (touch floor around clock)

D2 3x30sec Bicycle Crunches

E1 2x10ea Deadbugs

E2 2x10 Alternating Leg Lowers

Upper Body (no equipment):

A1 4x10 Push-Ups (2 second hold at bottom)

A2 4x510yd Box Bear Crawl

B1 3x10 High Plank Shoulder Taps

B2 3x15ea High Plank Mountain Climbers

C1 2x10ea Cat-Cows

C2 2x10ea Bear Overhead Reaches

D1 2x10 Prone Handcuffs

D2 2x15 Push-Up to Downward Dog

Mobility

Lower Body Mobility:

90/90s (Back heel up holds/ front heel up holds)

Ankle combat stretch

Pelvic tilts (anterior/posterior)

Froggers

Pigeon Stretch

Lizard w/rotations

Thoracic Mobility:

Quadruped T-spine rotations (Arm Straight)

Quadruped Handcuffs with rotation (one arm on low back like wearing handcuffs)

Reach, roll, lifts (lift from lower traps, not shoulders)

Thread the needle

Bridge w/rotations

Body weight windmills (can do half-kneeling as well)

Downward dog with thoracic extension

Shoulder/Scap Mobility:

Wall Circles

Scap Circles

Prone ITYLs

Hinged ITYLs (Pretend string is pulling wrists back)

Bridge w/rotation

Windmills (1/2 kneeling/standing)

Wall Presses

Core Work:

Planks (any variation) - challenge movement during plank more than time!

Wall dead bugs

Regular dead bugs

Bird dogs (don’t kick heel up, kick heel out!)

Reverse crunch

Leg lowers

Bicycle Crunches

Supermans

Arm Care:

Standard Warm-Up (3-4x per week)

1 set of 15-20 - J-Bands per day

x10 Reverse Throws - Black & Green

x10 Upward Toss - Green

x10 Pivot Picks - Green

x5 Walk Aways - Blue

x5 Roll-In - Blue

Extras:

Rock Backs - 2x - BRYG

Step Backs - 2x - BRYG

Bauer’s - 1x - BRYG

Walking Wind-Ups - 1x - BRYG

Catch Play - Do what you can do! Something is better than nothing!

Post-throwing:

2x10 Partner Reveres Throws - (B or G)

1x20 J-Band Reverse Throws

1x10 J-Band Y’s

2x20 Rebounders (G)

2x20 Band Pullaparts

These are simple things you can add if have somewhere to throw them into!

Light catch 2-4 days per week will help you maintain what you have built up! Something is better than nothing!

If you have questions, email prpbaseball101@gmail.com for more ideas or remote training!

Structured Return to Throwing Programming

Managing the calendar year for throwing athletes from off-season shut down periods to bullpen schedules preparing for season!

Everyone has their opinion on shut down periods and pitch counts. Yet, there are very few clear “return to throwing programs” to properly prepare the arm for the season. One thing is true, a piece of paper from a PT, Doctor, or coach given out to the all different ages, injury history, workload capacities, and movement patterns is not the right answer.

There is a common misconception with shut down time for throwing athletes and their build up to season. If you shut down for an extended period of time you need a slow and steady on-ramping for the arm, preparing your delivery, and pitch count.

This blog is written to help educate players, coaches, and parents on managing your off-season arm preparation. Before we go any deeper, if there is one thing that you take from this just know that every single arm is different with feedback, recovery time, arm stress and more. There are several different options and variables, some described below, that. can adjust your program to lead to healthy, strong season.

Listen to your arm. Listen to your body. Be consistent.

Adjust any throwing on-ramping program based on feel and comfort.

Key points:

Start with low volume and intensity following proper warm-ups. Build up volume, distance, and intensity over the course of 4-5 active days for 4 weeks before max output throwing.

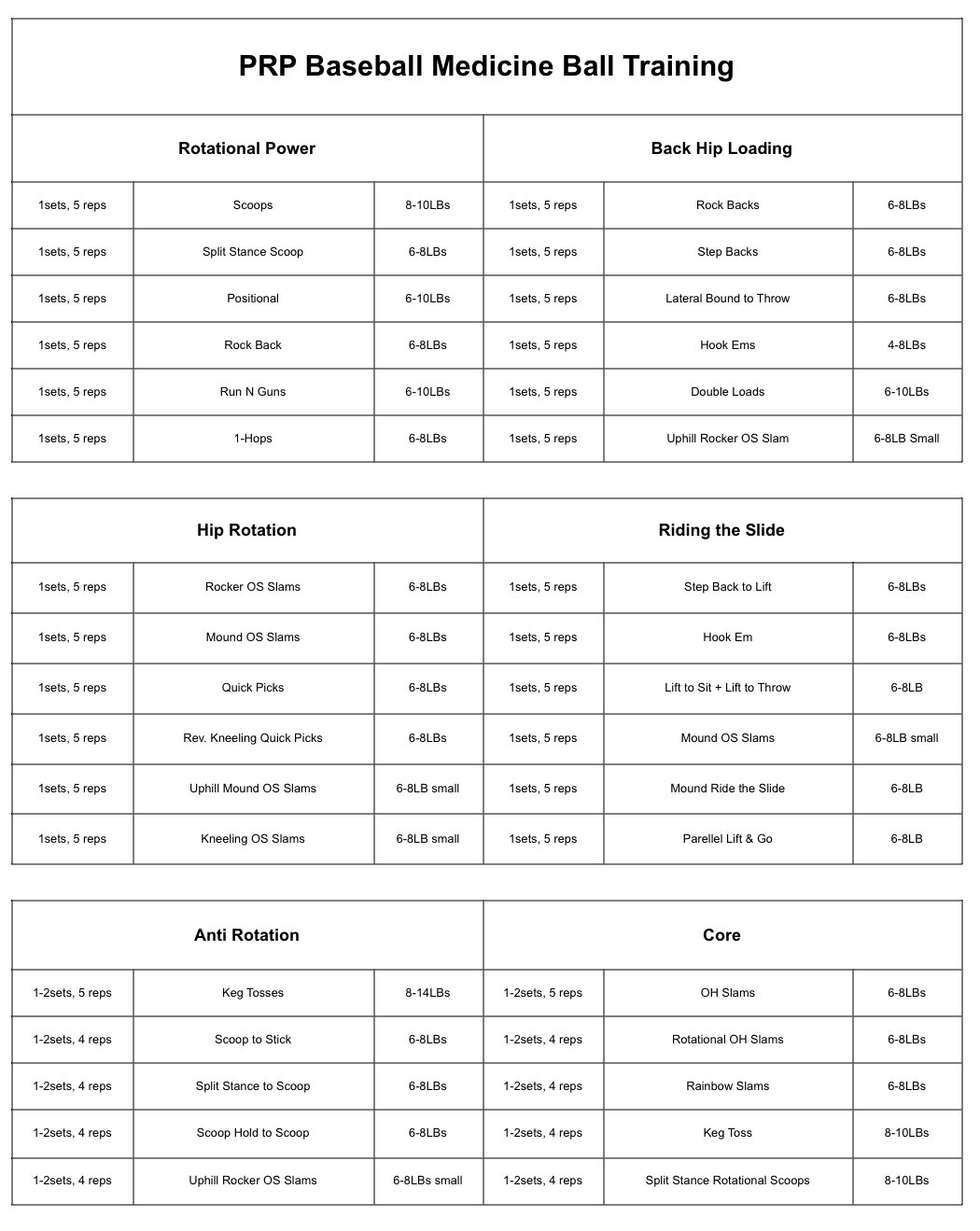

Before throwing begins, begin active ramping with jaeger bands, medicine balls, and weight training.

Distance is least valued in our opinion. Work to your comfort distance matching designated intensity for the day. This differs case by case.

You are not just on-ramping your arm. You are preparing your delivery each and every day. Make your reps count.

At the end of on-ramping, the arm should feel zero restrictions during warm-ups or long toss.

Quality reps, not just quantity.

What should shut down timeline look like?

This depends on several factors listed below. We look for 8 weeks of no baseball throwing. Personally, we want athletes continuing jaeger bands, consistent weight training, and some basic plyocare drills for at least 4 of these 8 weeks.

Factors:

Age - younger athletes should have longer shut d0wns.

Inning workload

Physical Maturity

Skill level

Velocity and Mechanics

Expected timeline for upcoming season

Injuries

Differences for Ages/Levels

In an ideal world for a HS athlete who has played from March through September, we should be shut down for 8 weeks in October and November. These months should be highly focused on getting stronger, managing body weight and mobility. Your 4-5 week on-ramping phase can begin the second week of December to give 14 weeks to prepare for HS season.

College athletes have several more factors and are more difficult to determine when to shut down. One part should be consistent, if you are shutting down then shut down for more than just 2-4 weeks.

If you are a spring-heavy inning workload arm then shut down for part of the summer and improve your strength, movement quality, mobility, etc. After this shut down you can prepare for fall season, deload after fall, and throw through November/December as you prepare for Spring.

If you do not throw much in the spring, you should find ways to get innings in during the summer. Ideally, you can shut down from mid-July through early September and on-ramp for end of fall season. Most coaches want every arm throwing in their fall season which is understandable but also has to fit their timeline for having a shut down in between spring seasons.

This is the same for professional pitchers. Ideally, the shut down begins as early in the fall as possible. Some professionals will shorten actual shut downs and keep work capacity low so they can continue working on simple aspects such as spin, movement efficiencies, and more.

Every professional is different and should have enough feel to understand their needs. Professional pitchers should have a longer bullpen build up to work on each pitch, build up work capacity, and review spin data.

Personally, I want every competitive pitcher to have a long, steady on-ramping phase with ample time for movement development, pitch design, and adjustments based on how arm feels. Rushing a pitcher back to competitive season is the worst thing for your preparation for the most critical part of your season, the playoffs.

How On-Ramping Should Look:

Schedule your on-ramping backwards knowing when you are expected to be “mound ready” or beginning a high-intensity throwing phase. Work at least 4 weeks back from there. Get your plan set, equipment needed, and set a consistent scheduled throwing time at a facility.

Have a structured warm-up from mobility, CARs, Jaeger Bands, to plyocare work. Your pre-throwing work is vital to restoring a repeatable and efficient throwing motion. Your post-throwing modalities are just as important as your warm-up. Execute them properly.

The 4 week plan is a steady increase of volume, intensity, and distance. At any point the soreness becomes uncomfortable, rest, then go back and do the previous day again. Do not move forward until level of soreness lowers. The goal is to only have slight soreness the day between throwing days with little restrictions on throwing days.

We use a player readiness scale to assess how we feel on a 1-5 scale, 5 meaning feeling great. We need to be at a 4-5 for it to qualify as a throw day during on-ramping. The players track their sleep, nutrition, stress, arm, and body readiness.

Plyocare drills should be tailored to the individual, but we try to keep some variety in the day to day throwing to challenge quality movement and feel with their own delivery.

For position players, we simply adjust plyocare drills from the mound to flat ground and have them work in their specific position movements (backhands, forehand, etc).

Each day and week should see increases in the intensity behind throws. We start our guys around 60% RPE (rate of perceived exertion) and build up to 100% at the beginning of week 4.

While some struggle with judging their intent, it keeps the mindset consistent with getting more aggressive each day. Some athletes will need to maintain a 75-90% RPE to stay connected and smooth in throwing motion.

PRP Baseball On-Ramping Program

Email us at prpbaseball101@gmail.com to receive the On Ramping Program!

From here, we make adjustments in throwing volume, intensity, and plyocare drills knowing their limitations and deficiencies. We strongly believe in this format as a “good start” to any on-ramping program for ages 13 and up.

We have already seen athletes crushing their previous velocity maxes at the end of this on-ramping program in their baseline testings.

General On-Ramping Recommendations:

Don’t pay much attention to distance. Focus on the intensity and staying connected. Ball flight should be true and consistent on way out to distance needed for the day.

Take an extra day of rest when needed. Goal is to get 16 throw days in 4-5 weeks.

Add jaeger bands, mobility, CARs, tubing, basic plyocare drills on days in between scheduled throwing days.

Basic plyocare drills - Reverse Throws, Upward Toss, Pivot Picks, Rebounders

If can’t throw outside at distance, set up throwing targets in the cage for having intent and purpose with each throw as you build up. (Hoops, tape, rope, etc)

Long Toss Phase Explained:

Alan Jaeger (@jaegersports) has praised long toss for years and how letting your arm breathe, taking it for a walk, or massage catch play can prepare your arm for battle. Instead of “limiting” throws or “saving bullets”, we should be trying to add bullets to the chamber. Long toss is a critical part of PRP programming during the off-season and monitored in-season for our athletes.

Alan Jaeger describing his style of Long Toss program.

There are several different beliefs in what long toss actually is. We follow Alan’s style with extension phase on the way out to comfort or max distance and then compressions on the way back in. Volume, distance, and intensity depend on the day and how the arm feels.

Extensions - High arc throws, have a hump on it, air underneath it, or massage throws as Alan Jaeger refers to.

Compressions - On-A-Line throws or “pulldowns” with a shuffle step as your partner comes back in to about 120-90 feet after extensions.

We want our athletes to have a minimum of 3 full long toss days before any “high-intent” or competitive throwing sessions tracked for velocity and we program our on-ramping that way.

Here is a full list and mini-breakdown of our plyocare drills used at PRP Baseball. Most of the drills you can see on our YouTube Channel.

In these drills, we are challenging different parts of the delivery from lower half patterning to arm action. Finding a handful of exercises that challenge yet promote better movement in your delivery is key for improvement throughout on-ramping.

Click the button above to view FREE videos.

The True On Ramping…

What happens in the weight room, on the floor in your mobility work, sleeping and eating enough, and improving movement sequencing is what will truly make your on-ramping lead to better numbers and production come competition time.

Your arm will only improve if everything else improves. The hand is the final part of the kinetic chain and conditioning the arm doesn’t solve movement deficiencies. This is why we spend time developing the movements before on-ramping begins as well as the strength and conditioning component to prepare the body for added throwing.

Our athletes go through certain CVB drills, med ball throws, and plyocare drills based on the needs of the athlete to improve control of the ground, hips, and their arm swing. This is more valuable than any piece of paper with throwing volume listed.

For example, we are focusing on low reps and more volume in the weight room to build strength and work capacity during our on-ramping. We also blend medicine ball drills into the pre-throwing work to work on movement sequencing and lower half mechanics.

Attention to Detail

The most overlooked and underappreciated aspect of developing younger baseball players is catch play. The high-level athletes play high-level catch. Every single time. Feeling out your movements, getting to consistent release points, feeling proper spin, and more can all be worked through during low-moderate volume catch play in your on-ramping.

If you are scattering the baseball and not repeating movements you worked on in your pre-throwing work then you are simply feeding the bad habits at the most important phase of your work day. This shouldn’t require coaches to harp on during catch play. This is expected in our athletes as it should be yours. Bad catch play leads to poor performance. Simple.

Besides catch play, we often see athletes who get bored with repetitive workouts, drills, and mobility/strengthening exercises. These drills are prescribed for specific reasons and can directly affect your game performance if executed well every day.

While new drills and variety can help challenge the CNS and keep athletes engaged, it is often the simple and specific exercises that are needed to change habits.

After You Finish On-Ramping

This can go several different directions for different ages, timelines, player needs. For most pitchers ages 15 and up, we would enter a pulldown phase with mound assessments. Plan would be to start assessing velocities both in pulldown and mound then setting modalities from there. Most would enter a 3-4 week velocity-based phase with pulldowns and high-intent bullpens.

Player A Example -

Day 1 - Velocity Day - Pulldown Assessment

Day 2 - Recovery - Core Velocity Belt (CVB), Video Review, Lower Lift, Arm Care

Day 3 - Hybrid - Light Long Toss, Medicine Ball, Hybrid Plyocare, CVB, Upper Lift

Day 4 - Hybrid - Mound Assessment - 10-15 pitches - Movement Lift, Video Review

Day 5 - Recovery - CVB, Medicine Ball, Drill Implementation

Day 6 - OFF Throwing, Lower Lift

Day 7 - Hybrid - Long Toss - CVB, Medicine Balls, Hybrid Plyocare, Drill Work, Upper Lifit

During this velocity-based phase, we want to implement drills (CVB, Med Balls, Dry Work, Plyocare) to focus on any deficiencies in our delivery. Mound blending occurs during high-intent phase but will become a bigger focus.

After few weeks off velocity-based programming, bullpens should increase in frequency and pitch count. Below is a simple, very adjustable bullpen schedule following a velocity phase:

Day 1 - Bullpen #1 - 1 set - 20 fastballs

Day 4 - Bullpen #2 - 2 sets - 10 fastballs, 5 change-ups

Day 8 - Bullpen #3 - 2 sets - 10 fastballs, 5 breaking balls, 5 change-ups

Day 11 - Bullpen #4 - 1 set - 10 fastballs, 5 breaking balls, 5 change-ups

Day 15 - Bullpen #5 - Hitter Standing In - 2 sets - 20-25 pitches each - Count work - First pitch strikes, 0-2/1-2 counts, 3-2 counts

Day 18 - Bullpen #6 - Hitter Standing In - 2 sets - 20-25 pitches each - Off-Speed Focus

Day 22 - Bullpen #7 - Starter - 3 sets - 20-25 pitches each / Reliever - 2 sets - 15 pitches

Day 26-27 - Bullpen #8 - Startere 3 sets - 20-30 pitches each - Live Hitters

Obviously, these days and amount of throws should be adjusted based on age, time to season, and how the arm is recovering!

In Conclusion

The most important thing to take from this is to have a plan. Write it down. Track progress. Make adjustments. If you follow everything from our information above with zero adjustments or progress tracked then you did it wrong. Listen to the arm. Listen to the body.

There are several variables going into a return to throwing program. If you are coming off an injury, be sure to run any throwing protocols through the person prescribing your workouts. It is very common for injury-based return to throw programs are too passive and do not have the ram ready for high-intent work.

If you are shutting down for an extended period of time be sure to follow a steady return to throwing program. The worst thing you can do is take an unconditioned arm into high intent work and expect it to last the season.

For questions, e-mail us at prpbaseball101@gmail.com!

Strength Training for Overhead Athletes

Visit this link to read a blog written by Steve Krah with Greg Vogt talking about how we train overhead athletes at our Bridge The Gap Conference! https://takeoutyourscorecards.wordpress.com/2019/11/20/prp-baseballs-vogt-talks-strength-training-for-overhead-athletes/

Developing an Efficient Thrower from the Ground Up

Developing an Efficient Thrower from the Ground Up

Overview:

Every company, coach, and social media guru has all of the answers for more velocity, command, and healthy arms… just ask them! This is not to prove or disprove certain companies. This is simply to share information that we use at PRP through video, Core Velocity Belt, Driveline equipment and drills, medicine balls, and the weight room. We will be discussing:

The importance of the lower half

How to assess it

How to train it

How to develop it.

There is a time and place for discussing and breaking down the arm action, glove-side disconnection, extension, and finishing position. But what if that was all (almost) a bi-product on how you stabilize and move through your lower half?

Build your foundation, make the ground your friend, and learn to rotate from the middle with a solid base. The ability to coil will have a large effect on your ability to uncoil!

Connection

The feet are often the most overlooked piece of the throw. The foundation, or base, begins with the arm-side foot. Most lose the battle before it begins. Better connection to the ground and longer we can hold that connection while internally rotating the rear hip, the better!

The 3 points of contact are shown here (image). The ability to ride the back hip while maintaining these points of contact help create more built up energy going into pelvic rotation.

What does “riding the back hip” or as we call it “riding the slope” mean? Take your arm-side hip away from your arm-side knee. Elite throwers are able to “sit” or “hinge” the arm-side hip away from arm-side knee with 3 points of contact in the arm-side foot!

Most pitchers have their weight in point #3 (shown image). This leads to being a quad-dominant rotator. They struggle to hinge, separate, and sequence their rotation from pelvis to trunk.

If you see this, have them remove the shoe and ask them to feel where weight is. We use the term “weight more” to feel more weight into the ground at all 3-points of contact.

What about after the load and hinge?

The foot should start to disengage from the ground once the rear hip begins internal rotation. The heel will follow the hip. As hip internally rotates, the heel will begin to come up. You’ll quickly learn most end up bailing off the heel and rotating into “point 3” much earlier than desired.

Into foot plant, the lead foot should land flat and firm into the ground. When lead hip finishes pelvic rotation, the lead foot should stay solid, firm in the ground. Once the pelvis is done rotating the feet have completed their service to transferring energy up the kinetic chain.

Ground connection leads you down two paths, connection or disconnection. The cause and effect from the feet into hips into trunk begins with how you grab the ground and resist rotation.

Drills to Feel Ground Connection:

Wall Drill - Feeling connection too ground + hinge/sit

Dry work with no shoes on (dry throws, lift & sit, lift & stride)

Wall Drill (shown right)

Uphill Mound Drills (throwing, med balls, dry work)

Med Balls + CVB Drill work

Standing Separations - Shoes on or off

Lift & sit (feel heel corkscrew)

Step Back to Lifts (dry/plyo/med ball)

Training movements in weight room - ex: KB Swings, Deadlift, RDL’s, Squat

Rotation

“Throw like a tornado through a doorway.”

Heard this quote at Pitch-A-Palooza and it stuck. We must rotate with efficiency and intent. But we must control our direction and be stable through rotation. Simple, yet complex.

Isolate the hinge and pelvic rotations with this activation drill.

Clean rotation begins with a good setup and pelvic stability.

Pelvis needs to rotate independently from the trunk.

The pelvis should fire before the trunk going into foot strike.

The pelvis should finish rotation before peak arm speed.

As we rotate the hips, the trunk should “whip” into rotation, bringing the arm along the ride.

This is a key reason why the ground connection and pelvic rotation are so vital efficient throwing. Without it, the trunk and arm are at the mercy fo the lower half.

Basic Drills with Core Velocity Belt - Hinge Separations, Standing separations, Stride and fire, and more. See free drills with CVB at -- https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL4zy_hzyhFTEiAJJaaNc332avdua1Ax8K (full list below)

Creating the Efficiency

Split Stance to Throw - Starting in hinge, holding that tension as work down slope.

Rotation and stability all begins with the hips and feet. Clean rotation comes from a stable environment to rotate in. These are areas to train daily and year-round. Athletes can feel and learn their lower half without the throw.

Coaches and athletes can build better movements to impact throwing mechanics during low or non-throwing periods.

How to Train the Lower Half?

Broad Jump is one way to assess lower half power. Training the lower half in the weight room can greatly affect power output in delivery as you continue to attack throwing movements.

This is a loaded answer, but will attempt to keep it directly to the point.

Learn “how” to properly hinge

Get strong

Train the the lower half in movement prep work with direct purpose. You can always add in Core Velocity Belt work to attack specific deficiencies and “feels”.

Medicine balls - Train in similar planes of motion with the lower half to feel power coming from “the ground up”.

Best piece of advice — Pay more attention to catch play with your athletes or yourself! Most instill bad habits with ground force and pelvic rotation during catch play. One example, watch step behinds when long tossing. Most complete the “shuffle” while on toes and end up throwing at a higher intensity with worse mechanics. You can adjust drills to make sure they have a chance to develop clean movements ro just continue too remind them the value of every throw.

How?

It is all about feel. Every “drill” or “constraint” is built around getting the athlete to feel the lower half working in the right patterns. We utilize the CVB (Core Velocity Belt) to challenge athletes to feel the pelvis and connection to the ground to control stable, repeatable movements.

We have optimized a list of drills and movements to put each athlete into different positions either pulling or resisting the CVB in their throwing movement. There is no magical drill that will fix each athlete. After assessing the breakdowns in efficiency, we prescribe drills and movements to challenge athlete to move more efficiently at specific stages of the throw.

Each day ends with putting it all back together. Athletes must feel the movements in the actual throw after drill work to reassess and we coach that feel back to the athlete.

Core Velocity Belt Usage

Each athlete begins with activations of the hinge and pelvic control through movement. After our hinge separations and standing separations, we progress to drill work with different anchors and levels of resistance to put athlete in better positions.

Athletes progress from activations to dry work to medicine balls to plyocare to mound/swing work. We must first feel the pelvic rotation and stability in activations. Each day starts with activating regardless of level. Some days will include more dry work or medicine balls. For example, on a lighter throwing workload day we will implement more med ball and Plyocare drills with belt on to replicate the delivery and challenges areas of concern.

Below is a breakdown of what drills and workouts we have athletes in PRP execute on a weekly basis. Every athlete will vary from these drills as needed and coached from our staff.

Medicine Balls

Edgertronic Med Ball Assessment

We implement medicine ball drills with all of our athletes for several reasons. Building rotational power, learning to rotate more efficiently, and intent to name a few. Athletes get several more repetitions each day of training without throwing a baseball yet still building proper movement patterns through medicine balls.

PRP prescribes different medicine ball drills based on the athlete’s needs to challenge movement efficiency through the medicine ball drills. If we can get 20-40 more throws a session through medicine ball work then we are getting more movement work without taxing the arm and building up a better mover to the throwing aspect of the session.

*E-mail prpbaseball101@gmail.com for a free list of medicine ball exercises and breakdowns

Uphill drills challenge rotation and “riding backside” more than flat/downhill.

Water Bag Usage:

The water bag has recently been added to our movement prep work to attack the lower half. We have 3-4 drills that we consistently use. All can be found on our YouTube Channel.

Single Leg Downhill Chops (shown)

Load and Hinge

Water Bag Throws

Variations of Throws - Inward Turns, Step Backs, Uphill, Quick Picks, etc.

These drills should be trained with specific purpose of controlling the overload and instability of the water bag. This will expose those who don’t control the ground and stay controlled from the trunk down.

*Learn more about our medicine ball results/blog here - https://www.prpbaseball.com/blog/2018/6/27/thecorrelation-between-med-ball-and-positional-velocity

Plyocare

Same as medicine balls, we utilize Plyocare drills and throws to create better movers. These are often done pre-throwing or as drill work in throwing for warm-ups, arm patterning, and feel of the delivery prior to their catch play. PRP has shared our different plyocare drills as a staple of our training. You can see more about our drills and why in our Blog (The What and Why of Plyocare).

Plyocare Drill - Parallel Feet - Ride back hip down slope.

We implement different drills and constraints through plyocare with the CVB on as well. Each athlete will have different drills prescribed using the belt and plyocare based on their needs.

Even without using the belt, cueing athletes to “feel” loading, hinging, and rotation during their rock backs, walking wind-ups, roll-ins, step backs and more will bring awareness to their throwing “mechanics”.

QB Drops - Added footwork from the Step Back and challenge the athlete to hold the hinge during load.

At the end of each day with using the belt in different ways, blend back to normal mound or positional throws without the belt.

*E-mail prpbaseball101@gmail.com for a free list of plyocare drills and breakdowns.

Adjusting Use of the CVB

Each athlete has specific deficiencies which should lead to different adjustments to drill work.

For example, going towards attachment on lead hip is much different than going away from attachment on lead hip. Going away challenges early hip rotation and lead leg bracing while going towards attachment pulls athlete down mound quicker and requires them to stay into back hip.

Another example - rear hip angled (shown under med balls) pulls the athlete into a deeper sit/hinge which challenges them to maintain good direction while staying into rear foot.

Going away from attachment to challenge early hip rotation and bracing front side.

Most will struggle understanding how much tension is needed or wanted. As Lantz (@lantzwheeler) says best, “Less can be more”. Controlling the resistance and stabilizing movements is more important than trying to build up a large amount of tension in the movements.

As mentioned before, there is no right way to use the CVB other than to assess and diagnose deficiencies and attack them through different angles and tensions. The more comfortable an athlete can get with added tension/pull from different angles, the more feel they will gain with their movements.

Catch Play

The most under appreciated aspect of developing better throwing athletes. We limit the time to throw, give little guidance on how to progress in catch play, and yell when it looks sloppy. Now, there are a million ways to instill a proper catch progression. We prefer a few staples in our catch play to focus on upper trunk rotation, arm action, and adding specific lower half movements as we move back into a long toss.

Catch Play Drills:

Opposite Knee Throws (for youth throwers mainly) - 10-25ft

Pivot Picks - 10-45ft

Roll-Ins - 45-60ft

Rock Backs - 45-75ft

Step Backs - 60-90ft

Walking Wind-Ups - 60-90ft

1-Hops - 90-120ft

Step Behinds (or in fronts) - 90-300ft - EXTENSION phase (high arc)

Step Behinds - 210-120ft - Pulldown Phase

*We often implement 9, 7, 6 oz in our light catch play drills do build up to the baseball weight. Some athletes will use these for long toss in certain capacities.

Coach the important aspects of catch play on a daily basis, especially early in the year/off-season. Preach building proper levels of intent (depending on the day), controlling release points, usage of the lower half and repeated arm action.

Personally, I am a big fan of getting youth athletes in athletic positions during catch play into nets or to a partner. Make them throw on the run, moving backwards, slow rollers, etc. The more they learn to be athletic and loose, the better. There is a right time and place for these added to your daily drill work!

The purpose of catch play is skill-development. One way or another, you’re developing a skill/habit on every throw. Make sure it’s done the right way!

Strength Training

This part of the blog is not meant to take a deep dive into strength training. We train athletes of all levels in the weight room and will adjust to each as needed, but to cover a few main points on what some “absolutes” are in the weight room:

Sumo Deadlift

Build strength in hips, trunk, glutes

Train anti-rotation

Challenge scapular mobility and strength with overhead movements

Get in the split stance, often.

The most overlooked component of training a throwing athlete is being in the frontal plane way too often. This means simply pressing, squatting, power clean, etc. We rotate for sport. We need to lunge, single arm press, single arm row, isolate shoulder/scap extension more.

By challenging single leg strength, anti-rotation, and learning to hinge… we can create a much more efficient mover with strength training.

Few recommended exercises:

Palloff Press (several variations)

KB Swings

Single Leg RDL

Reverse Lunge

Cable or Dumbbell Rows

Deadlift

Lateral Bounds

Alternating DB Press

1/2 Kneeling KB Windmills

Landmine Row to Press

Front Squat

TRX Overhead Raise to Reverse Fly (several variations)

Prone Cuban Press

By no means should you just remove bench press, squat, or power clean from your weight training. Strength and power matters. Most young (14-18y/o) athletes spend too much time in these movements and not enough in positions that translate. As an industry, we need to do a better job of providing proper foundations of strength, mobility, and stability training so that when they enter higher-level training and programs they have a strong base to build off of.

I strongly recommend that parents of young (11-14) year old athletes get their kids into quality strength training programs that focus on hinging, core stability, athletic movements, and make fun competitions during the training. Those that get a strong base and enjoy the weight room have bright futures in sport-specific skill development.

When discussing training for a high-level throwing athlete (say 85+ mph), we need to focus on challenging mobility, the decelerators, and explosive movements. Few key points on this:

Full range of motion in all exercises, controlled.

Challenge movements with different levels of constraints (single leg vs 2 leg, DB vs Cable, eccentric vs explosive, multi-plane movements)

Constant progress in resistance levels (weight/load)

Build up posterior chain, pulling exercises, grip, core (decelerators)

VBT - Moving weight for speed - Focusing on explosive movements from a lighter load

Throwing Velocity vs Trap Bar Deadlift (1RM)

Lastly, PRP has done a few generalized case studies on trap bar deadlift to throwing velocity and broad jump to throwing velocity. While neither are a direct correlation by any means, there were several similarities between those that were on the top of the scale for deadlift, broad jump, and medicine ball velocity and throwing velocity. This is a big reason we constantly train and assess our athletes in these movements. Building a stronger, more explosive athlete can lead to more efficient throwing.

Review

Developing throwing athletes requires several components to their development. First, get athletes to understand the importance of the lower half and it’s role in throwing. How you decide to develop those skill sets can be outlined above then choosing which areas of training impact each athlete individually.

The lower half shapes the upper half. The load shapes the finish. The release point is under the mercy of everything that happens leading to the release point. Build the first steps of the throw then fine tune the rest.

For more information on training the lower half, e-mail prpbaseball101@gmail.com.

The What and Why of Plyocare

What are plyocare balls?

Plyocare balls have become a popular training modality across all levels and ages of throwing athletes. These plyocare balls are simple rubber-coated weighted balls that are filled with a sand-like material. The weights range from 3oz to 4lbs depending on company/brand you use. The style of use has a large variety, from “holds” to general throwing conditioning to high-intent throws. They have been branded by major companies such as Driveline Baseball amongst other companies and are used worldwide for all ages of throwers.

Why do we use them?

The easy answer for using plyocare balls is for arm strengthening and conditioning. The actual reason for using them is adapting better movement patterns while conditioning the arm.

When training with overload and underload balls, the movement patterns adapt to the load and task. With certain styles of programming, they can be used for arm strengthening. The volume and style of throw can vary, but some specific drills mixed into general training program can have an impact on throwing velocity and the overall condition of your arm.

Personally, we are big believers in warming up to throw instead of throwing to warm-up. These “throwing” drills are restraint based drills that mix up the tempo, momentum, and allow important patterns to occur during the throw. By the time we are done with plyocare “drills”, the throwing “mechanics” should have already improved.

Another key reason is the improvement on feel and command. When throwing different balls of different weights, the body has to program release points each throw. Preaching the importance of commanding the plyo balls is key to their use. Athletes should retain the feedback on each throw from how they got to a certain release point.

The volume and effort within the throws is where coaching and programming become key. These weighted balls are not magical toys that will fix movement patterns or add velocity. Prescribing certain drills and managing the workload throughout the week around game days and bullpens is very important to healthy development.

How to implement plyocare to your program

Plyocare balls are best used as a pre and post throwing modality with different periodization of velocity training and arm maintenance. Warming-up with the basic shoulder activation drills and arm patterning throws are an easy add-in to your daily programming. This 5-minute pre and post programming can reduce injury and promote more efficient throwing patterns while leading to better catch play.

Basic drills include reverse throws, upward toss, rebounders, and pivot picks. These are widely used in programs across the nation. The main difference is how and when they are programmed at different age levels and programs.

We evaluate players movement patterns and prescribe drills specific to that athlete to attack their movements and feel. For example, an athlete who struggles with rhythm and tempo we will prescribe more walking wind-ups. If a player struggles with loading backside we will implement step backs or QB drops.

When and how much to use them is also a challenge that coaches face. This decision should be based of a few key variables. Time of year, athletes needs, and athlete feedback should be how you shape your programming.

Typically, off-season (winter) on-ramping should have more plyocare throws than in-season, with a bigger focus on high-intent. Tracking velocities and videoing movement patterns are great ways to develop throwers during the off-season.

Volume for off-season would typically be 5 days a week with 2 of those being velocity-tracking days. Volume for in-season would be 3-4 days with 0-1 velocity days depending on the athlete. Each day would consist of 2 or 3 movement patterning drills such as roll ins, walking wind-ups, quick picks, etc.

Key adjustments:

Athletes who are not competing on the mound regularly should add 1 day of high-intent plyocare.

Athletes who are doing pulldowns should limit high-intent plyocare to 1-2 days depending on comfort and conditioning level.

Give at least 2 days in between competitive bullpens and high-intent plyocare.

In-season pitchers not competing much should maintain 2 days of high-intent plyocare.

Athletes in return to throwing programs should monitor RPE and velocity closely as it should continue an upward progression.

Providing feedback with a radar gun and/or video is key to implementing plyocare properly. Some athletes struggle to control their RPE. Monitoring soreness week to week throughout return to throwing and off-season programs is key to manage stress workload with plyocare.

As stated before, a misunderstood aspect of using plyocare balls is the development of command and feel. Coach the importance of this to your athletes by having targets and competitions for hitting spots!

Take a deeper look

There are a few key components of plyocare use that often get overlooked. We know to focus on movement patterns, arm swing, etc. High-intent or low-intent, we gain feel for our arm, release point, and spin with the extra throwing drills within plyocare programming.

What we often miss is the spin of the plyocare ball. It is very common for throwers to cut (get around) the plyoballs. Pay attention to the spin off of the wall. The ball should bounce directly back to the throwing side if creating true backspin. When athletes throw the ball and it cuts across body, then the thrower immediately knows they got around the ball. If an athlete struggles with it during catch play, this can be a great time to work on staying behind the baseball.

Velocity readings for high-intent plyocare can be the best coach in the room. While managing different levels of intent, seeing feedback in number form helps both the athlete and the coach learn. There isn’t a magic formula for what to expect on velocity readings for different plyo drills, but you can learn from throw to throw and week to week how well you are moving and progressing. The simple goal should be to maximize the velocity of each ball between 1LB and 3.5oz on testing days. For Driveline PlyoCare balls, you should try to beat your positional velocity with the yellow ball in every throw.

Train the decelerators. The reverse throws and rebounders have become more commonly used because of this. Reverse throws are a great drill for posterior shoulder conditioning. Rebounds are equally important for force reception and training the forearm, bicep muscles. These are vital to controlling the arm during deceleration post-release.

Coach the deficiencies. When athletes struggle with specific movements in the throw, there are several drills to attack each pattern. There is a drill chart with a video playlist attached at the bottom of this blog for your use. For example; instead of telling a kid to drive his lead leg into the ground more (when he clearly struggles doing that), try having him do kneeling get ups or move the plyocare drill to going uphill (mound). This will challenge him to use the front leg better from adjusting the environment and task rather than listening to verbal cues.

Having a routine

There are a million ways to implement pre-throwing routines such as plyocare balls. The programming of drills, managing workloads, and individualizing drills is key but the comfort of your athletes going through a daily routine to improve their game is what matters most.

Be consistent. Be firm. Make it a priority.

Most programs get away from proper plyocare use simply because of practice planning and time management. There is always time, if it is a priority, to get the daily plyocare work in. Some days it may interfere with other important aspects, but the importance of arm health and having confident throwers often trumps the other practice modalities

Video it. Track it.

The radar guns and videos don’t lie. Use these as your direct communication to athletes on how well they are moving, managing their RPE, and monitoring their progress.

Summary

Plyocare has a large effect on the group of players for several reasons. Implementing a routine of “warming up to throw” or “earning the right to catch play” are key phrases I live by with my athletes. Developing movement patterns and arm conditioning with the same training tool is another key reason. For some athletes, is a great velocity training tool while most it provides another way to develop command.

Any way you look at it, plyocare use can develop more confident throwers by challenging them to throw more and throw better.

Free video playlist and drill chart below!

Plyocare Drill Demonstrations - https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL4zy_hzyhFTEx3Blr4XbN8HCeuoTgnMxT

For more information, contact prpbaseball101@gmail.com!

Follow us on Twitter @PRPBaseball101 and Instagram @PRPBaseball!

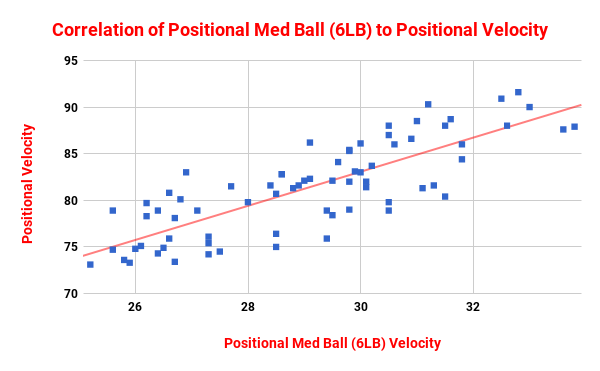

The Correlation Between Medicine Ball Run N Gun to Pulldown Velocity

The Correlation Between Medicine Ball Run N Gun to Pulldown Velocity

By Greg Vogt

Overview

Medicine Ball training is used in several facets to develop throwing patterns and rotational power. It is an underused tool for several age groups in their baseball development. One major tool used for both assessment and development is the “pulldown” throw. I recently posted two articles about the correlation of pulldowns to mound velocity, as well as mound medicine ball velocity to throwing mound velocity.

This third part of the blog relates to the means of building intent and rotational power through “run n guns” and how the athlete’s medicine ball velocity correlates to pulldown velocity. By presenting another assessment and training tool backed by data, us coaches can build a development plan that works.

What is the Medicine Ball Run N Gun?

The Run N Gun is a term used to describe a throw beginning with a running start to build up momentum. This throw typically has more velocity produced due to added momentum. The footwork for the pulldown and med ball run n gun should be about the same. This test can have a learning curve, which is part of the point for using the training tool, as an athlete learns to build intent and process their movements.

This movement requires the athlete to control energy transfer and put all of their intent into the medicine ball. The point of this assessment is to see how well an athlete moves and to evaluate their rotational power output. Data on this can provide a foundation for training programming to continue development for the athlete.

As referenced before, medicine ball velocity can be assessed in many ways. The positional movement (mound delivery for most) is another way to find out how well an athlete moves. The Run N Gun is a better way to truly assess both intent and rotational power at its highest form.

What is expected for the Medicine Ball Run N Gun?

The MB RnG is used to develop intent and rotational power. The velocity production ranges between ages. For high school athletes, the average velocity was 31.4mph. For middle school athletes, the average velocity was 27.6mph. The assessment was used with a 6 pound medicine ball. The footwork varied between athletes, but they were given 15-25 feet to build up energy before release. All throws tested must be with a shot put throw, meaning staying chest height with throwing arm pushing the back of the medicine ball.

For training, overload and underload weights can improve both movement patterns and intent. Video analysis should be conducted to use as a teaching tool for the athletes. As mentioned before, the style of the run n gun is up to the athlete, but it should be done with a clear focus on producing velocity. Mechanics and overcoaching can damage the intent from the athlete.

Data Tracking

The medicine ball velocity was assessed twice throughout the program. Testing included 5 throws with a 6 pound medicine ball. A shot put throw was required after desired footwork to build up momentum.

While the average was 31.4mph across the board, there are some numbers that stand out for the assessments when split up into different categories:

90+MPH pulldown = 33.5MPH MB RnG Average (23 athletes)

85-90MPH pulldown = 32.6MPH MB RnG Average (23 athletes)

84.9MPH > pulldown = 30.7MPH MB RnG Average (24 athletes)

Data shows the post-testing correlated to their pulldown velocity (5oz). The trendline shows an increase in throwing velocity compared to the medicine ball run n gun. While the medicine ball run n gun can show a quick increase in velocity with some practice, the correlation to the pulldown velocity stays consistent.

Why?

Assessing athletes is a key component to developing programs and proper training protocols. As mentioned before, the medicine ball run n gun is one way to assess intent and rotational power. To throw hard, you have to try to throw hard. Intent shapes more movement patterns than any drill.

Now, you must learn to maximize energy development from the whole body. Often, throwers rely on the top third of their body to put force into the baseball. This means learning to rotate from the ground up. When overloading the object being thrown, the body must program itself in the best way possible.

Athletes learn from the radar gun. The radar gun provides immediate feedback to each athlete specific to their intent and movement patterns. With the footwork and rotational components being so similar, the medicine ball run n gun gives both athlete and coach another assessment tool in the developmental process.

How to program it:

Medicine ball training can be mismanaged very easily. The workload around other training modalities becomes very important to the weekly stress management. A few general guidelines are to follow.

Medicine ball training can be done 3-4 times a week depending on other workload. If in a heavy volume training regimine, the volume of rotational power training should decrease.

In general, the workload should be higher in the off-season compared to in-season due to the amount of high intent competition throughout the week.

Choose 3-5 movements a day to focus on. At least 1-2 of those exercises should be general rotational movements, then 2-3 at a baseball specific movement.

Rest appropriately between reps. This is not cardio.

Each rep should be an explosive movement.

Video and analyze to check movement patterns.

Choose 1-2 days (depending on need) to focus on patterns/sequencing and less intent.

Avoid high intent or volume medicine ball days when testing throwing/hitting velocity.

Change the weight. The weight shouldn’t dictate the intent. Training one session with a lighter weight should see increased velocities and stress.

Measure consistently. Velocity should be tracked weekly.

PRP Med Ball Programming:

Email us for a free PDF!

Summary

When looking at the data, there is a consistent trend in those who perform a higher medicine ball run n gun to higher pulldown velocity. There are outliers. Key aspects of throwing such as arm patterning, sequencing, physical strength, and mobility can have a big effect on the correlation. But, if you are looking to choose a few specific drills that can have a direct impact on throwing velocity, the medicine ball run n gun should be one of those tools used on a consistent basis.

Training with intent is a must when developing power. Throwing is a rotational movement. Developing rotational power is key to developing throwing velocity. Medicine ball training is a great tool to developing rotational power. Keep the workouts specific to what you are trying to accomplish. Medicine ball run n guns are a way to assess athletes and develop their throwing velocity.

Implementing Pulldowns and the Correlation between Mound Velocity and Pulldowns

Implementing Pulldowns & The Correlation To Mound Velocity

By Greg Vogt

Overview

A hot topic in baseball training revolves around high-intent throws to develop throwing velocity. Often referred to as “pulldowns” or “run n guns”, these throws are used to train the body to move explosively and produce a high velocity while improving movement patterns. Several training facilities implement them while some are highly critical of them.

Texas Baseball Ranch and Driveline Baseball are two of the most popular training facilities that utilize this training modality as one piece of their arm conditioning and publicly support it with data. They have been very open and transparent with how high intent throws are incorporated into a complete approach of velocity development. That being said, it has been very controversial on social media with the baseball community and programs who believe in other styles of training.

A training environment must push the stimulus to or slightly past limitations so the body can adapt to higher levels. Ron Worforth noted in his recent article (Texas Baseball Ranch) that Paul Nyman emphasized “The Bernstein Principle - The body will organize itself based upon the ultimate goal of the activity.” When challenging the body to organize in a way that demands maximal output, the movement patterns and intent are often improved. This includes weight training, high-intent throws, and medicine ball drills. It goes much deeper than just pulldowns with this principle when teaching athletes the importance of intent and how the body moves at a high intensity.

Long Toss became a very common training tool thanks to Alan Jaeger’s programming (https://www.jaegersports.com) over the past 10-15 years. Although it is not a new training tool, it is used much more commonly nationwide and his education to athletes all across the country has been pivotal. As a part of long toss, compressions (pulldowns) come after the high-arc distance throws. While just one piece of a puzzle, the compressions have value to advance arm conditioning levels for both arm health and velocity. Several programs practice and believe in different phases of this programming.

The goal here is understand not only what pulldowns are but also why or how they should be used with athletes of different ages.

What are Pulldowns?

A pulldown is a throw made with maximal intent after building up speed in some sort of running start. Athletes use a variety of footwork to get to release. Some incorporate a shuffle step, some a full crow hop, but most often you see a running start into a crow hop when the most criticism occurs. The point is to throw the ball on a line as hard as possible, doing whatever is needed to get that level of intent.

The baseball community resorts to criticizing pulldowns in this timeline over past few years:

Pulldowns will get you hurt (disproven)

Not worth it (for who?)

It doesn’t translate (discussed below)

There has been data, studies, and blogs written about the use of pulldowns and what actually occurs. The most common source of information comes from Driveline Baseball where they have written multiple blogs with studies including use of the Motus sleeve to track the stress levels of intent throws.

Why Pulldowns?

Why use pulldowns? Throwers will program themselves to move as cleanly as possible when we are throwing with max intent. This doesn’t mean they will move perfect, but often their movement patterns will look better than they do in a coached setting. Most athletes are overcoached when trying to organize their bodies to throw hard.

Pulldowns are one way to let an athlete train in a loose and free environment. Building up the intent of just attempting to throw as hard as possible in a low volume setting has extreme value with developing athletes. Pulldowns let athletes get rid of all the mental and physical cues that coaches often cram into their minds.

Now, a huge aspect of doing pulldowns is evaluating the movements within them. Videoing, assessing, and communicating the movement patterns doing pulldowns is one of the best ways you can teach an athlete to move more freely. Some kids move much better in a pulldown. Some don’t.

Also, ASMI’s research has proven that it there is statistically insignificant difference on arm stress between doing pulldowns and throwing bullpens. (ASMI Research on Weighted Balls / Driveline Blog) Furthermore, Driveline has shown research that flat grounds can be more stressful than mound via data from the Motus sleeve. If no difference in stress levels, than we need to reevaluate what should be done to condition the arm for the stress workload of bullpens and flat grounds.

Regardless, implementing pulldowns into an arm conditioning program is just another teaching and training tool that is used in an environment that has the athlete training freely at a intent level that matches the game environment. There is more information below about how to program pulldowns into a conditioning program. More often than not, the dosage of a training tool is more important than the exercise itself. Pulldowns are a great tool, when managed properly, to develop intent and velocity.

Data

2021 Winter PRP Data

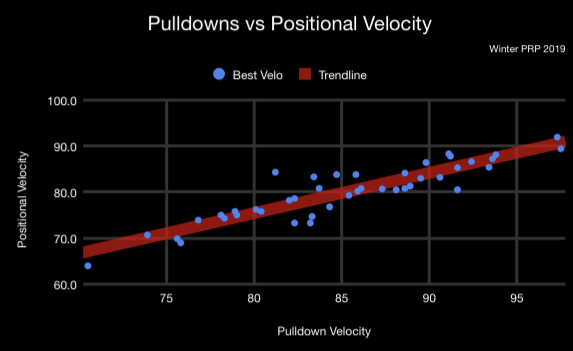

How and why do pulldowns correlate to mound velocity? In 57 pitchers who participated in the training program that included various amounts of pulldowns depending on the subject, there are direct correlations to velocity improvements based on age. Overall, there was a 6.1mph difference in pulldown to mound velocity. Each age group ranged between a 6.2 and 5.6mph difference, with 2018’s having the highest difference as well as the highest pulldown average velocity. The improvements in the high school program showed an average of 4.7mph in pulldowns and 3.4mph in positional velocity (15 of 72 were not tested as pitchers).

In 2020, our Winter PRP program had 112 athletes who consistently tested pulldowns and positional (mound or defensive position) velocity. This testing began after a 4-week on-ramping program. The final testing was after 10 weeks of training in March 2020. Data shows an upward trend in positional velocity based on their pulldown velocity.

Winter PRP 2020 Data

Result Analysis

Out of 93 members of the 90mph pulldown club, only nine are not currently committed or already playing collegiate baseball (as of July 2019). Three of those nine are under 17 years old and two decided to go to college without playing despite having an opportunity to play at other schools.

Does it translate?

2019 Winter PRP Data

2019 Data Breakdown

22 pitchers that pulled down over 90mph within the test group averaged 86.9mph in mound velocity

>94mph in pulldowns averaged 88mph on mound (10 pitchers)

<90mph averaged 78.7mph on the mound (35 pitchers)

<85mph in pulldowns averaged 75.6mph on mound (20 pitchers)

An important piece of this data for this program was to learn more about the athletes that have big or small gaps between pulldowns and mound velocity. The average difference was about 6mph between pulldowns and mound velocity. Several pitchers had gaps as big as 10mph or as little as 1mph. This information is key and should lead to adjustments in programming for each individual athlete. A kid who has a large gap is losing connection and energy transfer in his mound velocity. The pitcher who has little to no gap between pulldowns and mound is either breaking down mechanically during pulldowns or is lacking intent during them.

Once data is collected, the conversation is more supported with numbers rather than guessing why velocity is what it is. From here, the programming can be created and adjusted based on the data at hand.

2020 Data Breakdown

of 41 athletes who pulled down 90+, the average positional velocity was 87.6mph.

of 41 athletes who pulled down 90+, only 11 didn’t peak over 85mph for positional velocity.

The average positional velocity for 15 athletes who pulled down 94+mph was 90.1mph

The average positional velocity for 28 athletes who pulled down 92+ was 88.8mph

The average positional velocity for 26 athletes who pulled down 85-89.9mph was 82.4

The average positional velocity for 24 athletes who pulled down 80-84.9mph was 77.7mph

The average difference was 5mph between pulldown and positional velocity.

When to Use Pulldowns

Pulldowns have been proven to be useful to develop intent, movement patterns, arm conditioning, and velocity. Now, this doesn’t mean go out and follow a program of pulling down multiple times a week at age 13 without getting an assessment. Pulldowns should be properly placed in a throwing program structured with long toss, weight training, and a mechanical analysis.

Steps to take before entering the “pulldown phase” of arm conditioning:

Get assessed by a PT

Video Analysis on mechanics

Attack deficiencies of that assessment (ex: mobility, strength, throwing mechanics)

Complete 5-8 weeks of an on-ramping program including a long toss phase

Structured weight training program that includes 2-4 days a week

How to use Pulldowns in a structured way:

*Several factors could adjust the workload including age, maturity level, throwing workload, mound frequency, mechanical assessment, etc.

One time a week with 5-7 high intent throws at 100% intensity.

Include 3-4 other days of throwing between a low to moderate intensity

2-3 days rest in between moderate to high intensity throws

Structured weight training program that includes 2-4 days a week

By no means are these absolutes, but some simple guidelines on how to get into a throwing program with high intensity throws are important to follow the first time. Following a random online throwing program most likely won’t make you throw harder with an extreme risk for injury.

Summary

Developing throwing velocity should include a well-rounded training program to ensure that it is done the proper way. If certain areas are left out of training then the risk for injury can overtake the need for velocity. Several pieces of the training revolve around physical strengthening and athleticism. That being said, having pulldowns or high intent throws to develop both movement patterns and velocity should be one piece of the training.

As shown with data from several programs, the results of increasing pulldowns can also improve the mound velocity. The 57 pitchers shown in this study have an upward trendline with pulldown and mound velocity. Even the outliers can learn a lot about their deficiencies when tracking in a consistent, well-structured program.

Now, this doesn’t mean go throw baseballs hard until your arm falls off. This means that a properly structured training period following an assessment and on-ramping program can really lead you down the right path of velocity development.

For more information, e-mail prpbaseball101@gmail.com

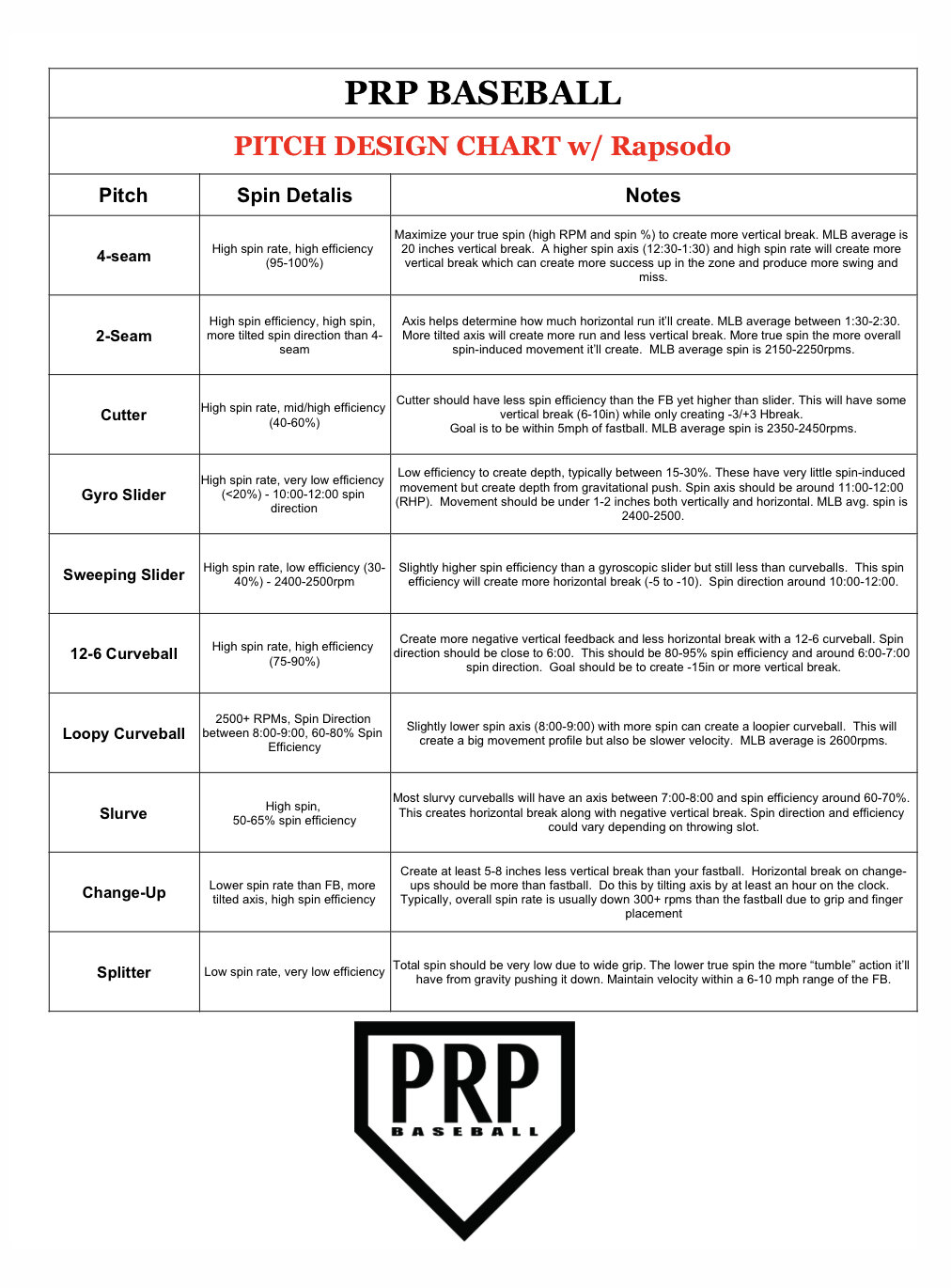

Pitch Identity and Design with Rapsodo

Overview

It’s 2020. Coaches have access to spin rates, horizontal break, and percentages of pitch types thrown in specific counts at the collegiate and professional levels. It’s time we stop telling pitchers to “pound the knees”. It’s time we stop calling every over-the-top breaking ball a 12-6 curveball. With products like Rapsodo, we have the ability to fully design and develop a pitcher’s arsenal.

What is Rapsodo? Rapsodo is a pitch tracking device that analyzes spin rate, velocity, movement, command, and provides the ability to break down mechanics. It provides immediate feedback on every pitch along with bullpen reports to analyze data from each training session.

Running, throwing, and bat speed all become bigger factors as you move to the next level. Scouts bring 3 things to a game; something to write on, a radar gun, and a stopwatch. You must check off boxes to gain attention from scouts and most of them come from a radar gun and a stopwatch.

"Throwing strikes and creating hard contact in the batter’s box is always going to be important, but bat speed, throwing velocity, and foot speed are still king."

Throwing velocity is the most important tool in the tool box. The other two most important pieces for pitchers are command and movement. You need to have at least 2 of the 3 to stand a chance being successful at the next levels. Velocity doesn’t solve all of a pitcher’s problems, but it is a very important box to check off for scouts and recruiters. When developing the other two pieces, Rapsodo becomes a critical measuring tool for pitchers.

We are in an era where pitchers are throwing 90+mph off-speed pitches with elite horizontal and/or vertical break. For example, Blake Treinen is throwing 96-100mph sinkers that look like a left-handed pitcher throwing sliders. These major league clubs are utilizing pitch tracking data to maximize velocity and movement to create weak contact. Below is information on what pitch tracking means, how to digest it, and most importantly how it can maximize your success in-game.

What does Pitch Tracking mean?

Pitch tracking data comes from different tools like TrackMan, Rapsodo, FlightScope, and Diamond Kinetics that provide different metrics for every pitch thrown. Some only track spin rate, movement, and/or velocity. Most major colleges, almost all MLB clubs, and higher end training facilities have products like Rapsodo to use for off-season, spring training, and throughout the season. TrackMan is in several Division 1 stadiums as well as every MLB stadium. This data gets crunched by employees and companies such as BaseballSavant. Data analysts, coaches, and pitching coordinators are using this data to digest performance along with enhancing pitch design, pitch development, and pitch usage for their players. More data below in this article shows different spin rates for MLB Pitchers.

What Does Rapsodo Do?

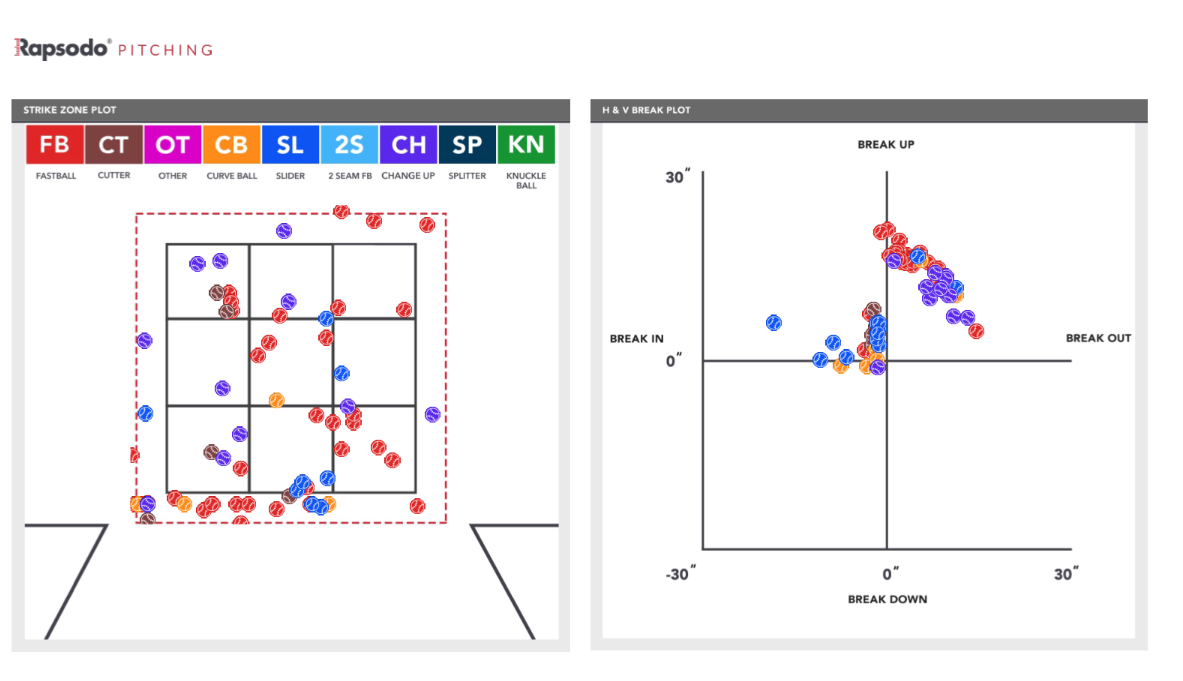

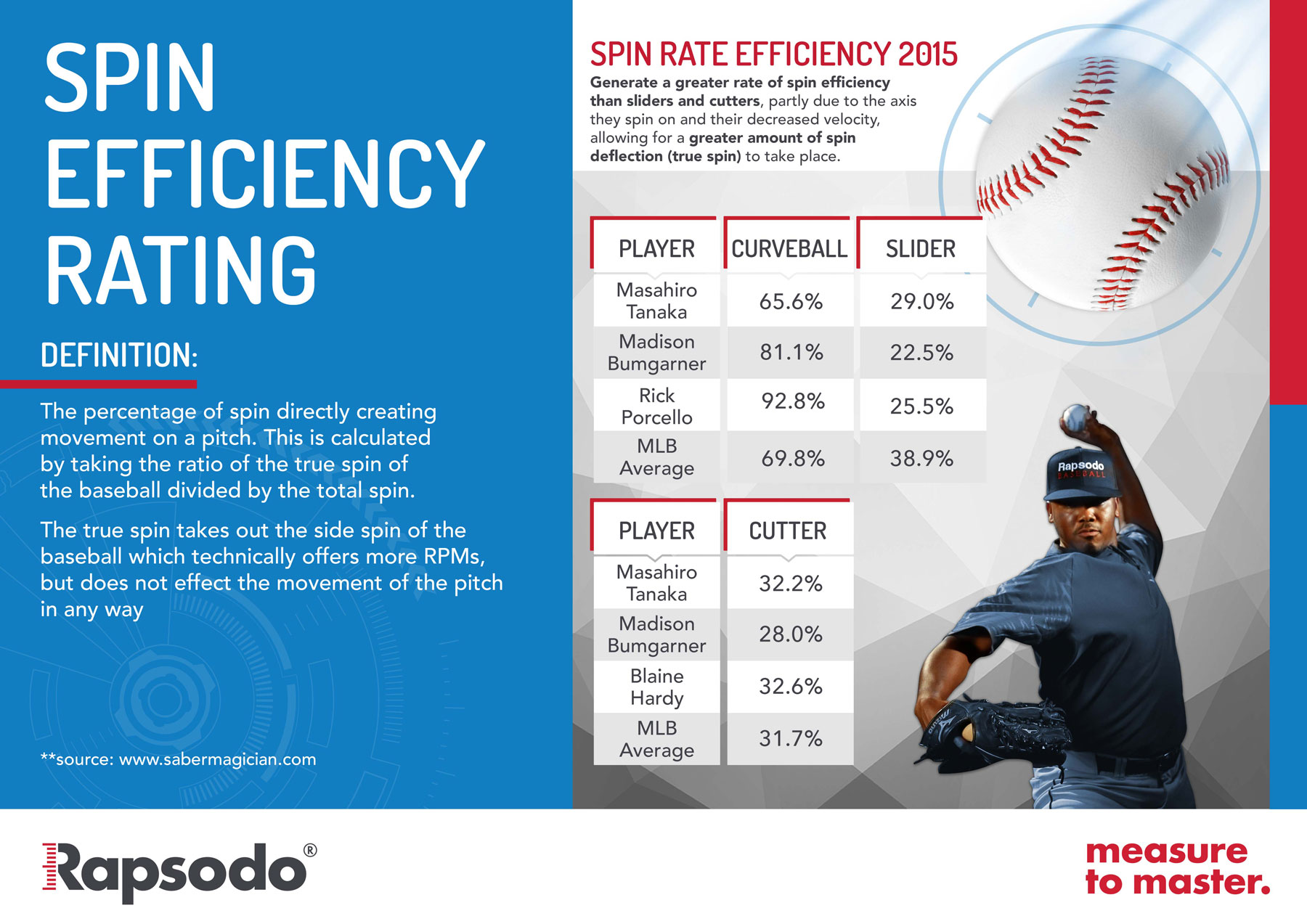

Rapsodo has provided a product that allows us to measure everything about a pitch including velocity, spin axis, spin rate, spin efficiency, and movement while supplying reports to analyze for coaches and players. See below (Image 1), you can identify your pitches, track your velocity and command, and work on creating the best movement for your pitch arsenal (Image 2). In Image 1, the charts on the bullpen report show strike percentage for different pitches along with horizontal and vertical break of every pitch.

Image 1

Image 2

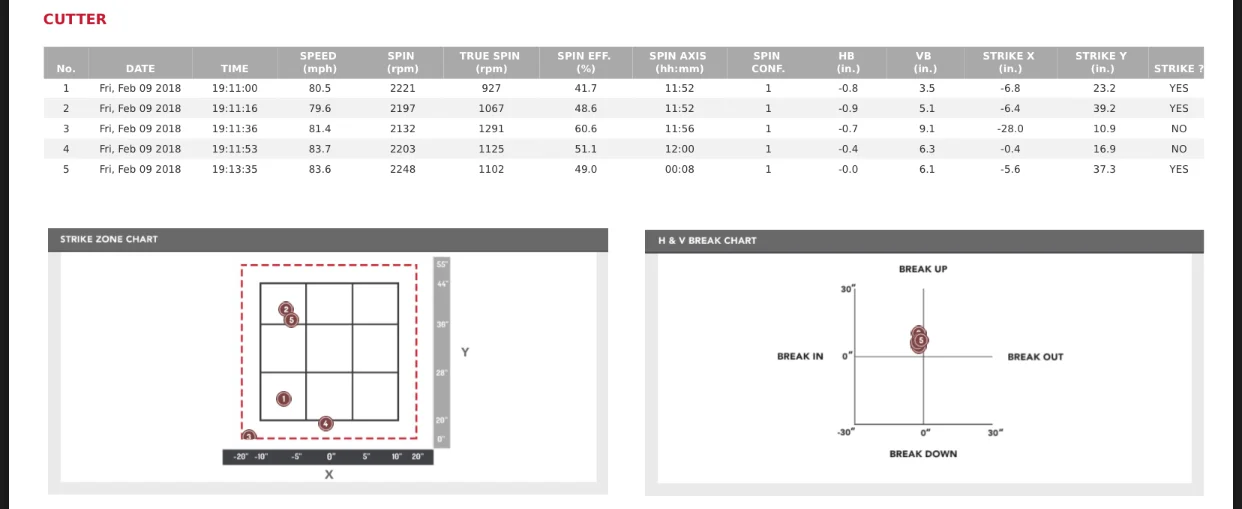

Pitch Data - Cutter - RHP

This small sample size of information is from one short bullpen that shows what is being done with the Cutter. Without this immediate feedback, pitch design becomes much more difficult to match the pitcher’s feel along with data. The Cutter shows it is moving on two different planes with little horizontal movement from spin. Two of the biggest factors are finding the consistency with axis and spin efficiency. Several key things can be abstracted from this data to apply to pitchers of all levels. The conversation between coach and player becomes much more supported by information rather than guessing. Trial and error is ultimately the best route to designing a pitch. If all we are relying on is the naked eye and video, then our rate of success will suffer.

Rapsodo can be used for all ages and skill levels, but should be a priority when working with higher level athletes who are wanting to maximize pitch efficiency. Movement being one of the key factors in pitch ability, you can get a full breakdown of your pitch arsenal in each bullpen.

Image 3

Data Usage

Now, how do we use the data? Rapsodo does a great job of supplying data. But the data means nothing without considering all factors. Pitchers generate spin and movement thanks to several variables such as delivery mechanics, slot, intent, grip, pressure distribution among fingers, etc. Just because Cy Young winners produce “x” type of spin rate does not mean you should aim to match. Numbers are different and unique to each pitcher. Your individualized skill set can be maximized in a completely different way than your peers.

For example, we know that a high spin rate fastball should be used in the top of the strike zone. It fights through gravity better which can is maximized at top of zone (Magnus Force). A low spin fastball should be kept down in the zone as gravity will drive that pitch down and produce more ground balls. With breaking balls, a heavy spin curveball with high efficiency can create heavy tilt and depth. A high spin, low efficiency (below 60%) will have less vertical break but could produce more horizontal movement depending on the axis. A slider from a low ¾ slot with low spin and efficiency will feature more depth from the gyrospin which can produce a high swing and miss rate. A high ¾ slot slider with heavy spin and low efficiency can produce the same result despite different grip, slot, and axis.

Point is, don’t aim for a “goal” on spin rate, axis, or efficiency. Collect data and analyze what is best for your delivery, grip, slot, spin, and tunnelling off of your other pitches.

"Every pitcher is an artist."

How you create your final product can be done in many ways with success. The goal needs to be that it is a repeatable, natural delivery with confidence to maximize soft contact or swing and misses.

Digesting Current MLB Data

With all of the data collection in the MLB these days, we can start to digest the importance of velocity, spin rate, movement, and the results they produce. Data shows that there are several outliers and differences between results and spin rates.

"We know that there is not one single way to develop more spin rate (legally), but there are ways to maximize pitch success within a pitcher’s current capabilities with spinning the baseball."

MLB pitchers feature different spin rates despite great results:

Yu Darvish - Fastball (4-seam) - 2564avg RPM

Gerrit Cole - Fastball (4-seam) - 2450avg RPM

Lance McCullers Jr - Fastball (4-seam) - 2301avg RPM

Bartolo Colon - Fastball (2-seam) - 2085avg RPM

Marcus Stroman - Fastball (2-seam) - 2245avg RPM

Justin Verlander - Curveball - 2803avg RPM

Clayton Kershaw - Curveball - 2364avg RPM

Charlie Morton - Curveball - 2835avg RPM

Sonny Gray - Curveball - 2890avg RPM

Madison Bumgarner - Curveball - 2356avg RPM

Seth Lugo - Curveball - 3337avg RPM

Andrew Miller - Slider - 2625avg RPM

Chris Sale - Slider - 2395avg RPM

Luis Severino - Slider - 2687 avg RPM

Carlos Martinez - Slider - 2185avg RPM

Max Scherzer - Change-Up - 1511avg RPM

Marco Estrada - Change-Up - 2026avg RPM

Johnny Cueto - Change-Up - 1520avg RPM

Kyle Hendricks - Sinker - 1932avg RPM

Jake Arrieta - Sinker - 2259avg RPM

Blake Treinen - Sinker - 2385avg RPM

Jordan Hicks - Sinker - 1985avg RPM

The average spin rate for a fastball in 2019 was 2300rpm for RHP and 2250 for LHP in the MLB.

Source: BaseballSavant

These examples show different spin rates that accomplish the same goal. The efficiency, axis, and slot are what is most important and make the biggest impact on the pitch movement. It’s easy to say that maximizing spin rate can better a pitch. When discussing breaking balls, that could be true when predicting the ceiling of a pitch. But to keep it simple, the goal is to manipulate the baseball with spin and movement. How you accomplish that can vary from subject to subject.

More spin data from 2019 MLB:

2S - 2150-2250rpm

CH - 1700-1800rpm

CB - 2500-2600

Cutter - 2350-2450

SL - 2500-2600

Splitter - 1400-1500

Here is a great link for Rapsodo breakdown for MLB spin averages and understanding the readings - https://rapsodo.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/MLB-PitchingGuide.pdf

Image 4 (via @mike_petriello on Twitter)

Image above (Image 4) shows that an increased spin rate and velocity can correlate to a higher swinging strike percentage.

Yes, higher fastball velocity leads to more swinging strikes. Image 4 shows data proving that higher spin rates combined with velocity usually equal more swinging strikes as well. Velocity and spin rate are also somewhat correlated. Typically a spin rate will climb with the velocity of the pitcher. Average RPM’s vary at all age levels along with velocity.

With the MLB average being 2264 in 2016 on the 4-seam fastball, this provides a general baseline for how pitchers should attempt to control the zone. High spin rate fastballs should be utilized in the top of the strike zone. Low spin rate fastballs should be utilized in the bottom of the strike zone. Those aren’t absolutes, but in general it provides a common approach that leads to weak contact. Typically, identifying a low spin rate on a 4-seam fastball leads to designing a 2-seam fastball to utilize less true spin and creating even more kill on the vertical break.

Bauer Units

Driveline Baseball posted a Blog in March of 2017 about Bauer Units.

Bauer Units = Spin Rate (RPM) / Velocity (MPH)

This equation provides coaches of all levels easier ways to compare data whether you are a big leaguer or a 14u pitcher. The MLB average was 23.9 Bauer Units. For example, a 72mph fastball at 1750RPM would be 24.3 Bauer Units (Driveline Baseball). When assessing younger athletes or lesser velocities, the Bauer Units formula is a great tool to truly assess where a pitcher stands in comparison to others. This clears up a lot of misunderstandings when working with mid-80’s HS/College pitchers with spin rates around 2,000. A pitcher throwing 84mph at 2100 will have 25 Bauer Units. This information and formula is very important when using Rapsodo for younger pitchers.

Design It

Once you have your pitch profiles, it is time to see what needs maximized while staying within your natural abilities. Here are some measurables for spin efficiency and spin rate to try to combine:

How do you design it? Knowing your spin and axis is step number one. Once you know, it becomes a trial and error process. Adjusting grips, wrist angle, pressure on fingers, and thumb placement are just a few to mention. Each pitcher has different hand and finger size. It takes time and a lot of repetitions. Pitchers must be able to “feel” release and the adjustments on the spin when learning how repeat a pitch. Inconsistent data on Rapsodo is very common when trialing a new grip or pitch. An inconsistent pitch in a bullpen setting is a set up for failure in game when it comes to pitch execution.

There are several ways to drive pitchers towards feeling differences in grip, pressure and release. Making too much of a change one way or another will make it very difficult to find a comfort zone for the pitcher.

Know your data? As mentioned before, this alone is critical to understanding where and how you should be using your arsenal. If you are a high RPM or Bauer Units 4-seam Fastball pitcher, you should be working up in the zone. If you are in the “average” category, you should trial with some adjustments in grip, pressure, and assess your 2-seam spin rates. Below average spin rate, you should be working in the bottom of the zone.

"Most pitchers have never been told to work up in the zone due to the misunderstanding of pounding the knees having a correlation to success. "

Few tips:

If want to throw a harder, higher spin rate off-speed pitch, turn it late and hard. Resisting early hand torque or “fall off” can create a higher velocity and/or spin rate. To keep coaching it simple, think fastball longer before breaking it.

Move your fingers closer together on 4-seam and 2-seam. Several pitchers create a cut action on the baseball as fingers being setup wider on the baseball allows middle finger to pull the side of baseball.

Try pressuring different fingers. Emphasize the middle finger more on a slider than a cutter. Emphasize the pointer finger more on 2-seam and sinkers.

Move the thumb! The thumb does a lot to affect spin. Notice different movements and spins on change-ups, sliders, cutters, 2-seam, 4-seam when tucking the thumb.

Collect video! Must match what you see with what you feel. Slow-motion video of behind the throwing hand will allow you to see what you may or not feel causing the results of the pitch spin and movement.

Be open to suggestions. Not one way works for just one guy. Don’t give up on a new grip or pitch just because you fail the first few reps.

These are just a few staples in developing a new pitch with or without a pitch tracking device. When using a Rapsodo in the bullpen, you can get immediate feedback whether or not moving grips or pressure changed anything with the pitch result.

Peyton Gray creates about 13-15in less vertical break on change-up compared to his fastball by tilting the axis and killing spin.

One of the biggest successes that I’ve personally had with teaching new grips and pitches is the change-up. Pitcher’s want to slow their arm action to ensure lower velocity than fastball. The change-up grip should be something that can be thrown with intent and comfort. The grip and axis will do the work while the delivery and the arm action should think fastball. The goal is to create a lower axis (2:30-3:00 for RHP) that produces lower efficiency than the fastball. This will kill velocity, create depth, and horizontal break. Typcially, this means a true spin of about 500-800 less than the pitcher’s fastball. Grips vary between pitcher’s mechanics and arm slot, but a common cue I personally use is throwing the the thumb and middle finger through the catcher’s mitt. This can motivate the pitcher to create later pronation and enhance intent. Again, this is just one example but have found success with pitcher’s at different levels.

Rep It