Implementing Pulldowns and the Correlation between Mound Velocity and Pulldowns

Implementing Pulldowns & The Correlation To Mound Velocity

By Greg Vogt

Overview

A hot topic in baseball training revolves around high-intent throws to develop throwing velocity. Often referred to as “pulldowns” or “run n guns”, these throws are used to train the body to move explosively and produce a high velocity while improving movement patterns. Several training facilities implement them while some are highly critical of them.

Texas Baseball Ranch and Driveline Baseball are two of the most popular training facilities that utilize this training modality as one piece of their arm conditioning and publicly support it with data. They have been very open and transparent with how high intent throws are incorporated into a complete approach of velocity development. That being said, it has been very controversial on social media with the baseball community and programs who believe in other styles of training.

A training environment must push the stimulus to or slightly past limitations so the body can adapt to higher levels. Ron Worforth noted in his recent article (Texas Baseball Ranch) that Paul Nyman emphasized “The Bernstein Principle - The body will organize itself based upon the ultimate goal of the activity.” When challenging the body to organize in a way that demands maximal output, the movement patterns and intent are often improved. This includes weight training, high-intent throws, and medicine ball drills. It goes much deeper than just pulldowns with this principle when teaching athletes the importance of intent and how the body moves at a high intensity.

Long Toss became a very common training tool thanks to Alan Jaeger’s programming (https://www.jaegersports.com) over the past 10-15 years. Although it is not a new training tool, it is used much more commonly nationwide and his education to athletes all across the country has been pivotal. As a part of long toss, compressions (pulldowns) come after the high-arc distance throws. While just one piece of a puzzle, the compressions have value to advance arm conditioning levels for both arm health and velocity. Several programs practice and believe in different phases of this programming.

The goal here is understand not only what pulldowns are but also why or how they should be used with athletes of different ages.

What are Pulldowns?

A pulldown is a throw made with maximal intent after building up speed in some sort of running start. Athletes use a variety of footwork to get to release. Some incorporate a shuffle step, some a full crow hop, but most often you see a running start into a crow hop when the most criticism occurs. The point is to throw the ball on a line as hard as possible, doing whatever is needed to get that level of intent.

The baseball community resorts to criticizing pulldowns in this timeline over past few years:

Pulldowns will get you hurt (disproven)

Not worth it (for who?)

It doesn’t translate (discussed below)

There has been data, studies, and blogs written about the use of pulldowns and what actually occurs. The most common source of information comes from Driveline Baseball where they have written multiple blogs with studies including use of the Motus sleeve to track the stress levels of intent throws.

Why Pulldowns?

Why use pulldowns? Throwers will program themselves to move as cleanly as possible when we are throwing with max intent. This doesn’t mean they will move perfect, but often their movement patterns will look better than they do in a coached setting. Most athletes are overcoached when trying to organize their bodies to throw hard.

Pulldowns are one way to let an athlete train in a loose and free environment. Building up the intent of just attempting to throw as hard as possible in a low volume setting has extreme value with developing athletes. Pulldowns let athletes get rid of all the mental and physical cues that coaches often cram into their minds.

Now, a huge aspect of doing pulldowns is evaluating the movements within them. Videoing, assessing, and communicating the movement patterns doing pulldowns is one of the best ways you can teach an athlete to move more freely. Some kids move much better in a pulldown. Some don’t.

Also, ASMI’s research has proven that it there is statistically insignificant difference on arm stress between doing pulldowns and throwing bullpens. (ASMI Research on Weighted Balls / Driveline Blog) Furthermore, Driveline has shown research that flat grounds can be more stressful than mound via data from the Motus sleeve. If no difference in stress levels, than we need to reevaluate what should be done to condition the arm for the stress workload of bullpens and flat grounds.

Regardless, implementing pulldowns into an arm conditioning program is just another teaching and training tool that is used in an environment that has the athlete training freely at a intent level that matches the game environment. There is more information below about how to program pulldowns into a conditioning program. More often than not, the dosage of a training tool is more important than the exercise itself. Pulldowns are a great tool, when managed properly, to develop intent and velocity.

Data

2021 Winter PRP Data

How and why do pulldowns correlate to mound velocity? In 57 pitchers who participated in the training program that included various amounts of pulldowns depending on the subject, there are direct correlations to velocity improvements based on age. Overall, there was a 6.1mph difference in pulldown to mound velocity. Each age group ranged between a 6.2 and 5.6mph difference, with 2018’s having the highest difference as well as the highest pulldown average velocity. The improvements in the high school program showed an average of 4.7mph in pulldowns and 3.4mph in positional velocity (15 of 72 were not tested as pitchers).

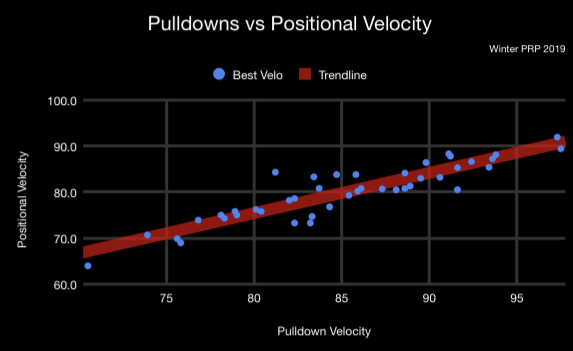

In 2020, our Winter PRP program had 112 athletes who consistently tested pulldowns and positional (mound or defensive position) velocity. This testing began after a 4-week on-ramping program. The final testing was after 10 weeks of training in March 2020. Data shows an upward trend in positional velocity based on their pulldown velocity.

Winter PRP 2020 Data

Result Analysis

Out of 93 members of the 90mph pulldown club, only nine are not currently committed or already playing collegiate baseball (as of July 2019). Three of those nine are under 17 years old and two decided to go to college without playing despite having an opportunity to play at other schools.

Does it translate?

2019 Winter PRP Data

2019 Data Breakdown

22 pitchers that pulled down over 90mph within the test group averaged 86.9mph in mound velocity

>94mph in pulldowns averaged 88mph on mound (10 pitchers)

<90mph averaged 78.7mph on the mound (35 pitchers)

<85mph in pulldowns averaged 75.6mph on mound (20 pitchers)

An important piece of this data for this program was to learn more about the athletes that have big or small gaps between pulldowns and mound velocity. The average difference was about 6mph between pulldowns and mound velocity. Several pitchers had gaps as big as 10mph or as little as 1mph. This information is key and should lead to adjustments in programming for each individual athlete. A kid who has a large gap is losing connection and energy transfer in his mound velocity. The pitcher who has little to no gap between pulldowns and mound is either breaking down mechanically during pulldowns or is lacking intent during them.

Once data is collected, the conversation is more supported with numbers rather than guessing why velocity is what it is. From here, the programming can be created and adjusted based on the data at hand.

2020 Data Breakdown

of 41 athletes who pulled down 90+, the average positional velocity was 87.6mph.

of 41 athletes who pulled down 90+, only 11 didn’t peak over 85mph for positional velocity.

The average positional velocity for 15 athletes who pulled down 94+mph was 90.1mph

The average positional velocity for 28 athletes who pulled down 92+ was 88.8mph

The average positional velocity for 26 athletes who pulled down 85-89.9mph was 82.4

The average positional velocity for 24 athletes who pulled down 80-84.9mph was 77.7mph

The average difference was 5mph between pulldown and positional velocity.

When to Use Pulldowns

Pulldowns have been proven to be useful to develop intent, movement patterns, arm conditioning, and velocity. Now, this doesn’t mean go out and follow a program of pulling down multiple times a week at age 13 without getting an assessment. Pulldowns should be properly placed in a throwing program structured with long toss, weight training, and a mechanical analysis.

Steps to take before entering the “pulldown phase” of arm conditioning:

Get assessed by a PT

Video Analysis on mechanics

Attack deficiencies of that assessment (ex: mobility, strength, throwing mechanics)

Complete 5-8 weeks of an on-ramping program including a long toss phase

Structured weight training program that includes 2-4 days a week

How to use Pulldowns in a structured way:

*Several factors could adjust the workload including age, maturity level, throwing workload, mound frequency, mechanical assessment, etc.

One time a week with 5-7 high intent throws at 100% intensity.

Include 3-4 other days of throwing between a low to moderate intensity

2-3 days rest in between moderate to high intensity throws

Structured weight training program that includes 2-4 days a week

By no means are these absolutes, but some simple guidelines on how to get into a throwing program with high intensity throws are important to follow the first time. Following a random online throwing program most likely won’t make you throw harder with an extreme risk for injury.

Summary

Developing throwing velocity should include a well-rounded training program to ensure that it is done the proper way. If certain areas are left out of training then the risk for injury can overtake the need for velocity. Several pieces of the training revolve around physical strengthening and athleticism. That being said, having pulldowns or high intent throws to develop both movement patterns and velocity should be one piece of the training.

As shown with data from several programs, the results of increasing pulldowns can also improve the mound velocity. The 57 pitchers shown in this study have an upward trendline with pulldown and mound velocity. Even the outliers can learn a lot about their deficiencies when tracking in a consistent, well-structured program.

Now, this doesn’t mean go throw baseballs hard until your arm falls off. This means that a properly structured training period following an assessment and on-ramping program can really lead you down the right path of velocity development.

For more information, e-mail prpbaseball101@gmail.com