How to Train the Lead Leg Block

What is a lead leg block?

The lead leg block is the entity in the delivery that redirects the force generated from the back leg, up the kinetic chain to the upper body. The “block” happens when the lead foot has contacted the ground and sends the lead knee from a flexed position to an extended position. To do this, the pelvis rotating into the lead hip requires lead leg to stabilize and extend to a certain degree. Ideally, a good lead leg block is timed up before and into ball release, not after.

Flexion to extension is a big contributor to throwing velocity, thus is why we will be discussing topics on how to identify, and how to prescribe based on what tools you have to fix the lead leg block.

Can a good lead leg block improve command? Yes. The ability to stop forward and rotational energy in the lead leg sends more energy to the trunk, shoulder, hand. The more efficient the lead leg, the increased ability for the thrower to maintain direction of the trunk and the hand to deliver the ball where it’s intended to be.

HOW TO KNOW IF A LEAD LEG BLOCK IS “GOOD”

Although not all lead leg blocks are created equal there are ways to tell if a block is great versus poor. We realize not everyone has a pitching lab to identify precisely what velocity your knee is moving to extension at, however looking at side video of the delivery and provide decent context to if you are timing up the lead leg block well or not.

For most hard throwers, the lead leg is stable and extending before ball release. Stability in the lead leg may be visually different when evaluating pitchers but the keys to look for are:

Foot/ankle stability — The foot lands and stays glued to the ground without changing direction or rolling over during the throw. (ex: lead foot lands then turns more to glove side as throw is being made (bad).

Lead knee stability — The foot lands and the lead knee stacks on top of the foot and stays there. Lacking lead knee stability would show the lead knee gets outside of the foot or continues moving forward as the throw is being made. A good lead knee would visually show the knee stop moving forward or east-west after lead foot hits the ground.

Lead hip stability — When the left foot and knee have began stabilizing after foot plant, the lead hip should also stop moving laterally and stack over the front foot during lead leg extension.

Below is an Ohtani video from side view to show the amount of force and quickness in his lead leg bracing. Does your lead leg do this? If it does, we ultimately want to reach max extension as fast as possible once our foot gets in the ground. The ability to send energy up the trunk into the arm requires a quality lead leg block prior to to ball release.

HOW TO KNOW A LEAD LEG IS BAD

On the opposite side of this discussion is how to determine if a lead leg block is bad. If your knee flexion stays the same at foot plant, or even continues to gain flexion (you sink even more into your leg as you move down the mound), this move typically does not correlate to strong velocity numbers, due to the negative correlation to redirect force at all, let alone with any sort of speed.

If you continue to go into flexion after foot plant, there is an opportunity for improvement. There are several factors that lead to a poor lead leg. The lowest hanging opportunities lie within prep work on the hips, mobility, single leg strength, rotational power, and ground force production.

Where does the energy go after the throw? Are the spinning off glove side? Typically, lead leg needs to improve if so.

Is the rear leg folding underneath? Typically, lead leg is falling more into flexion and needs improved.

Is the lead foot spinning while the throw is still being made? Typically, lead leg needs to improved by attacking foot and ankle stability.

Correlation of lead leg block to velocity

Here is where we dive into the math side of this discussion. Driveline Baseball has done many studies with their motion capture lab, both to prove and disprove how the lead leg block correlates to velocity.

When comparing lead leg reaction forces at the arm cocking stage, and arm acceleration stage, they found that the r^2 was strongly correlated with ball velocity at values from .45-.61. They had concluded that peak lead leg ground reaction force during the arm cocking phase was the best predictor of ball velocity.

This study was done for comparing the strongest correlator to velocity between the lead leg and drive leg, but that is a discussion for another day.

How we approach fixing issue

Now since we know the data is on our side, how do we go about fixing the issue here at PRP? From a mobility standpoint, we help you achieve those end ranges of motion by prescribing a movement assessment to find out why you move the way you move, and how we can make it better.

From there, our strength director will see how the athlete moves and produces force in the weight room (testing with Hawkin Dynamics). These numbers are an indicator of how much force the athlete may create on the mound. Then, we include patterning, single leg, and rotational work in the weight room.

The rest of our typical day plan is where all of the patterning of the delivery gets done, with the Core Velocity Belt, medicine balls, plyo ball drills, and actual throwing, which I will go into detail there. All drills being discussed will be linked at the end of this article.

How we prescribe with the Core Velocity Belt

For the lead leg, we have many different drills to offer that can be worked on with the Core Velocity Belt (CVB). One of the many great things that this tool has to offer, it can challenge and assist an athlete to get in virtually any position within the delivery.

Using another stimulus to challenge the athlete’s upper half (A PVC pipe, water bag, water ball), we will set up with the band on our lead hip, band behind, working away from the tension. Allowing the CVB pull the lead hip, creating an exaggerated amount of extension, over time with different variations of these drills will create a more natural lead leg block.

How we prescribe with Medicine Balls

The medicine ball is a tool that allows us again to pattern our lower half, without stressing the arm with throws, so we utilize them as often as we see fit.

A great way to challenge the lead leg block with med balls is actually by throwing up the mound instead of down the mound. An over the shoulder uphill slam with a medicine ball is one great drill we utilize in order to effectively pattern a better lead leg block.

How we prescribe with plyo drills

At this stage of the patterning workout is where we truly incorporate the upper half with the timing of the blocking that we have been working on in pre-throw skill work.

An example of one of our exercises that we utilize to get an easy feeling with arm timing and the lead leg would be a rocker throw. This drill focuses strictly on the lead leg plant. Making an emphasis on solely the lead leg creates a more controlled output when trying to pattern arm timing to the block.

Another variation for plyo throws in more constrained position in the split stance throw. This challenges lead leg stability and trunk rotation in prep work.

Higher level throws are often prescribed drop steps with med balls and plyo throws to improve the lead leg.

Summary

Ultimately, the lead leg is the stabilizer for the lower body to send energy to the upper body to rotate quickly. There is a strong correlation to ball velocity from lead leg flexion to extension velocity. It also improves strike throwing. The more force you can put in the ground, stabilize, and efficiently redirect the flow of energy from the ground up, likely will create a higher ball velocity.

The drills and methods outlined are only a few that we have to offer an athlete. There are several drills and weight room exercises that you can provide athletes to improve their lead leg patterns. There is no one singular way in how to train a certain movement pattern. At PRP, we challenge the athlete accordingly to receive the output we want.

Written by Max McKee

References

Boddy, K. (2022, August 30). Efficient front leg mechanics that lead to high velocity. Driveline Baseball. https://www.drivelinebaseball.com/2015/12/efficient-front-leg-mechanics-that-lead-to-high-velocity/

Developing A Change-Up

Learn How To Develop The Change-up Using Trackman And Rapsodo:

Below you will see some key aspects on change-up pitch design, assessing spin metrics, and how to develop it.

Designing Your Change-Up

The change-up is a crucial pitch in the arsenal of pitchers at all levels. Players should learn grips and practice it at an early age to improve feel and trust with it as they develop. It is often underused and misunderstood by amatuer pitchers. It will continue to develop the more you use and practice.

Change-ups are lethal due to their difference in velocity but similar appearance of spin/release. The best change-ups maximize movement along with speed differential and slot/release similarities.

A quality change-up is a great tool to have in your arsenal to get hitters off hunting your fastball. When used correctly, the change-up will impact hitters timing to improve your fastball success as well.

It can be misunderstood that change-ups should be slowed down intentionally to create deception. The goal is to be consistent with arm speed, slot, and finish.

Let the grip and spin direction create the movement, not changes in your delivery!

Spin Rate:

Spin rate for a change-up varies based on grip, spin orientation, and slot.

The goal is to create less vertical break and more horizontal break with the change-up. This can be achieved in several ways but more spin does not mean better movement.

Most change-ups have about 500-800 less true spin (rpms) than the player’s fastball. While this varies, lowering the true spin will ultimately create less vertical break due to less spin induced movement. For example, if a pitcher has about 2200 true spin on his fastball then getting to around 1500-1700 is a good start to killing vertical break.

A change-up can have a similar spin profile to the fastball but you will want to see the axis be tilted to the arm side to kill vertical break and add horizontal break.

We will discuss more about the spin direction/axis below, but the spin rate is going to vary between pitchers and is not as important as the axis it spins on.

Spin Axis:

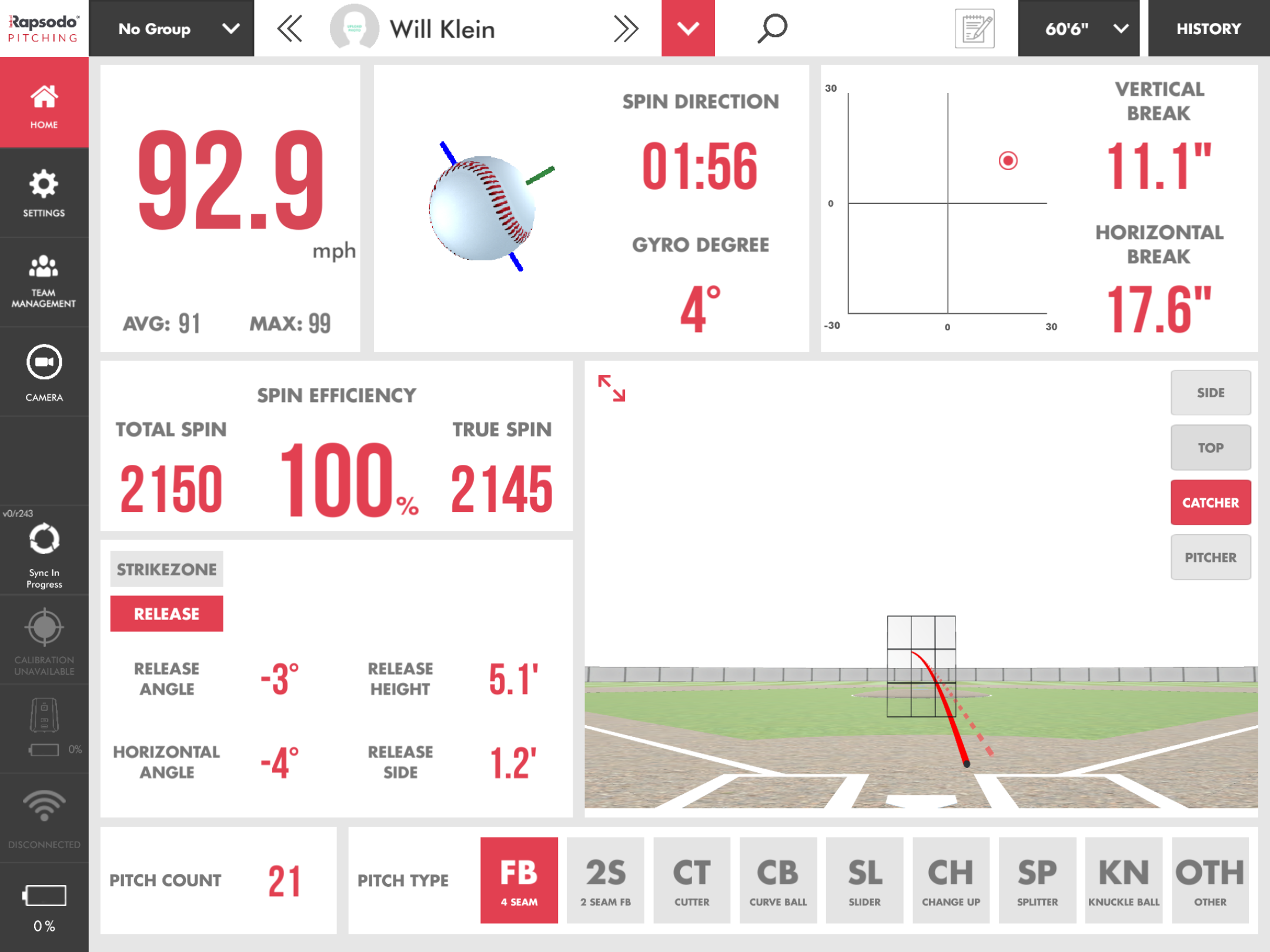

The best way to create less vertical but more horizontal movement profile on the change-up is by tilting the direction/axis it spins on. Notice the difference between these two images at “spin direction”.

The fastball has a 00:20 axis (almost directly over-top) while the change-up is tilted over two hours. This creates a huge differential between 4-seam and change-up movement profiles. The 4-seam has 20.2V/3.6V and change-up has 5.1V/14.2H. While have above 90% spin efficiency, one creates almost no vertical break due to coming out of a much more tilted axis. You can also see that the release angle, release height, horizontal angle, and release side numbers are almost exact same. This shows they should tunnel well out of his hand.

While this is a drastic example of a professional pitcher who specializes with the change-up, it gives a good presentation of what the differences between FB/CH should show.

When looking for valuable data on change-ups with Rapsodo, begin with the movement profile and spin axis.

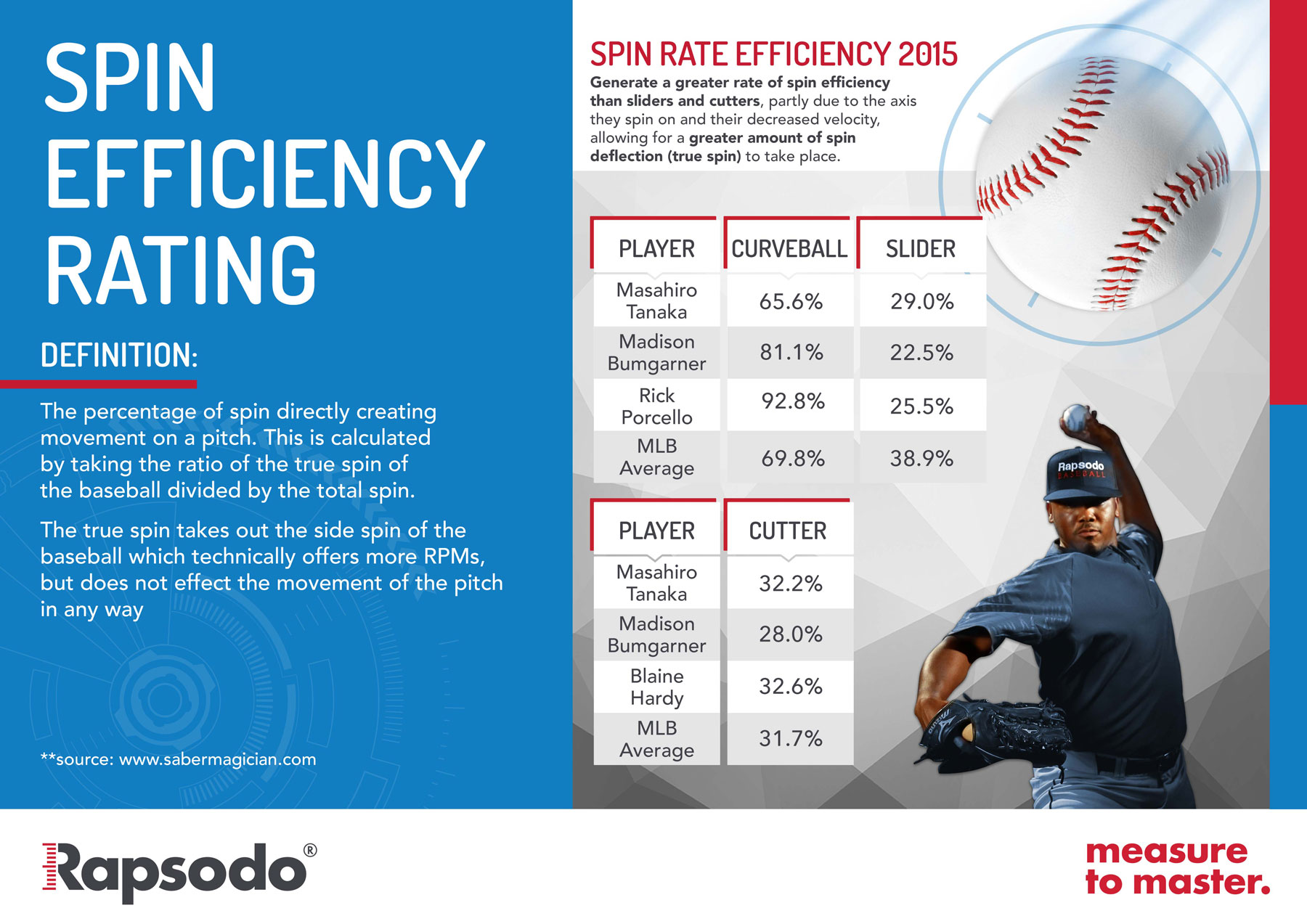

Spin Efficiency:

The goal is still to create a high spin efficiency on the change-up. There are times that change-ups can have lower spin efficiencies and be successful because of their ability to kill vertical break. Lower efficiency means less true spin which creates less vertical break. However, this hurts the amount of horizontal break (run) it would create. If we can keep the efficiency high and tilt the axis, then the horizontal break will be high.

Most high-level change-ups will have about 95% spin efficiency.

Spin Metrics

As mentioned above, overall metrics will vary from all different types of pitchers and levels. The important data comes from the metrics shown in differences of spin axis, vertical and horizontal break profiles. Messing with different grips, seam orientations, and cueing the finish in different ways can improve metrics.

Shown above -- This Change Up has about 8 inches more horizontal and 8 inches less vertical break from the fastbal due to a tilted axis (from 1:00 FB to 1:54 on CH), less spin rate, high efficiency and more release side.

Coaching the Change-Up:

Grips will vary between ages, arm slots, hand sizes, and more. The circle change is most commonly used, but can also be used in different ways. We recommend starting with these grips below and seeing which ones feel comfortable.

A common cue is “throwing the inner half” or “throw the thumb down” at the finish can but every pitcher receives those cues differently. Personally, I encourage players to emphasize maintaining fastball arm speed and throwing through the middle finger. Another cue we use is to “keep the palm inside the fingers”. This can help create a more angled spin direction.

Pressure on middle finger and thumb is a good place to start with those learning the change-up.

High-speed video and review can really advance the process on what is happening compared to what the pitcher feels happening. You can also use an iPhone slow motion zoomed in to release point.

Achieving more horizontal break than vertical break consistently with the change-up is a good goal to have when assessing movement with Rapsodo and Trackman. The main ways this can be achieved are:

Tilt the axis to arm side

Kill spin rate

Less release height, more release side (may lose tunnelling).

As previously stated, look for 5-8 inches less vertical than your fastball and 5-8 inches more horizontal than your fastball. Every pitcher will be different in achieving this due to arm slot, fastball spin axis, and overall spin rates.

Training the Change-Up:

Throw it! Use it daily in your catch play. We recommend 10-25 change-ups on all hybrid or higher intent throw days regardless of bullpen.

You can get these reps in after you’ve extended your catch play to distance. At about 150-120 feet for HS/College aged arms, do shuffle step throws with your change-up on a line. Add 2-3 throws every 15-20ft on the the way back in. Younger athletes can do this at 75-60 feet.

If working on the spin, throw it into a net about 50-60 feet away to see the angle and movement on it. The more you work on maintaining arm speed and throwing it downhill, the better!

For more information email us at gvogt@prpbaseball.com!

Pitch Identity and Design with Rapsodo

Overview

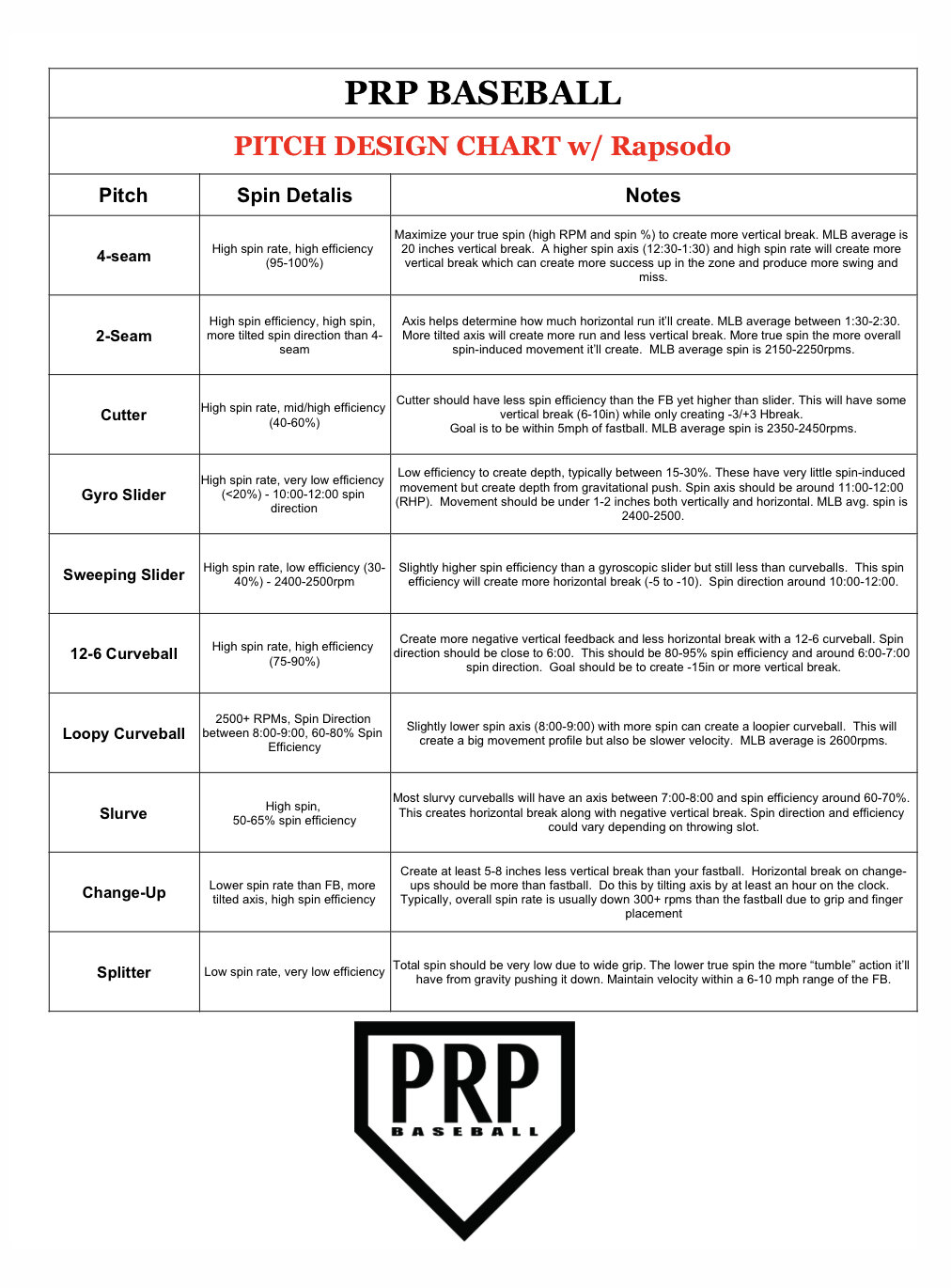

It’s 2020. Coaches have access to spin rates, horizontal break, and percentages of pitch types thrown in specific counts at the collegiate and professional levels. It’s time we stop telling pitchers to “pound the knees”. It’s time we stop calling every over-the-top breaking ball a 12-6 curveball. With products like Rapsodo, we have the ability to fully design and develop a pitcher’s arsenal.

What is Rapsodo? Rapsodo is a pitch tracking device that analyzes spin rate, velocity, movement, command, and provides the ability to break down mechanics. It provides immediate feedback on every pitch along with bullpen reports to analyze data from each training session.

Running, throwing, and bat speed all become bigger factors as you move to the next level. Scouts bring 3 things to a game; something to write on, a radar gun, and a stopwatch. You must check off boxes to gain attention from scouts and most of them come from a radar gun and a stopwatch.

"Throwing strikes and creating hard contact in the batter’s box is always going to be important, but bat speed, throwing velocity, and foot speed are still king."

Throwing velocity is the most important tool in the tool box. The other two most important pieces for pitchers are command and movement. You need to have at least 2 of the 3 to stand a chance being successful at the next levels. Velocity doesn’t solve all of a pitcher’s problems, but it is a very important box to check off for scouts and recruiters. When developing the other two pieces, Rapsodo becomes a critical measuring tool for pitchers.

We are in an era where pitchers are throwing 90+mph off-speed pitches with elite horizontal and/or vertical break. For example, Blake Treinen is throwing 96-100mph sinkers that look like a left-handed pitcher throwing sliders. These major league clubs are utilizing pitch tracking data to maximize velocity and movement to create weak contact. Below is information on what pitch tracking means, how to digest it, and most importantly how it can maximize your success in-game.

What does Pitch Tracking mean?

Pitch tracking data comes from different tools like TrackMan, Rapsodo, FlightScope, and Diamond Kinetics that provide different metrics for every pitch thrown. Some only track spin rate, movement, and/or velocity. Most major colleges, almost all MLB clubs, and higher end training facilities have products like Rapsodo to use for off-season, spring training, and throughout the season. TrackMan is in several Division 1 stadiums as well as every MLB stadium. This data gets crunched by employees and companies such as BaseballSavant. Data analysts, coaches, and pitching coordinators are using this data to digest performance along with enhancing pitch design, pitch development, and pitch usage for their players. More data below in this article shows different spin rates for MLB Pitchers.

What Does Rapsodo Do?

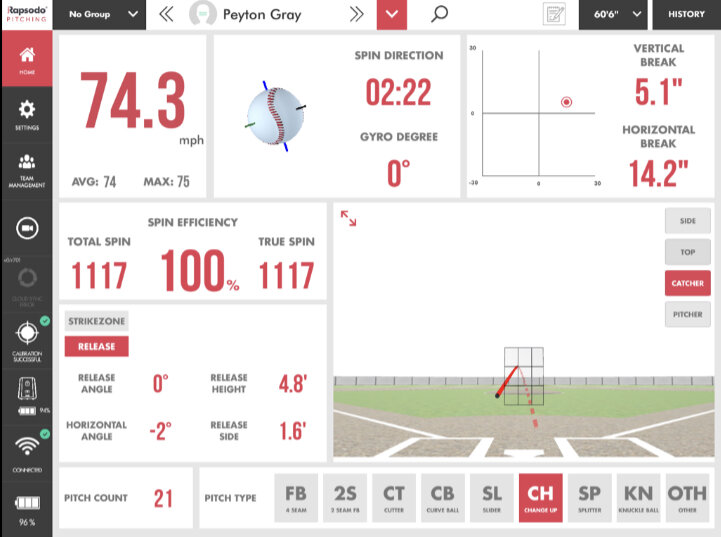

Rapsodo has provided a product that allows us to measure everything about a pitch including velocity, spin axis, spin rate, spin efficiency, and movement while supplying reports to analyze for coaches and players. See below (Image 1), you can identify your pitches, track your velocity and command, and work on creating the best movement for your pitch arsenal (Image 2). In Image 1, the charts on the bullpen report show strike percentage for different pitches along with horizontal and vertical break of every pitch.

Image 1

Image 2

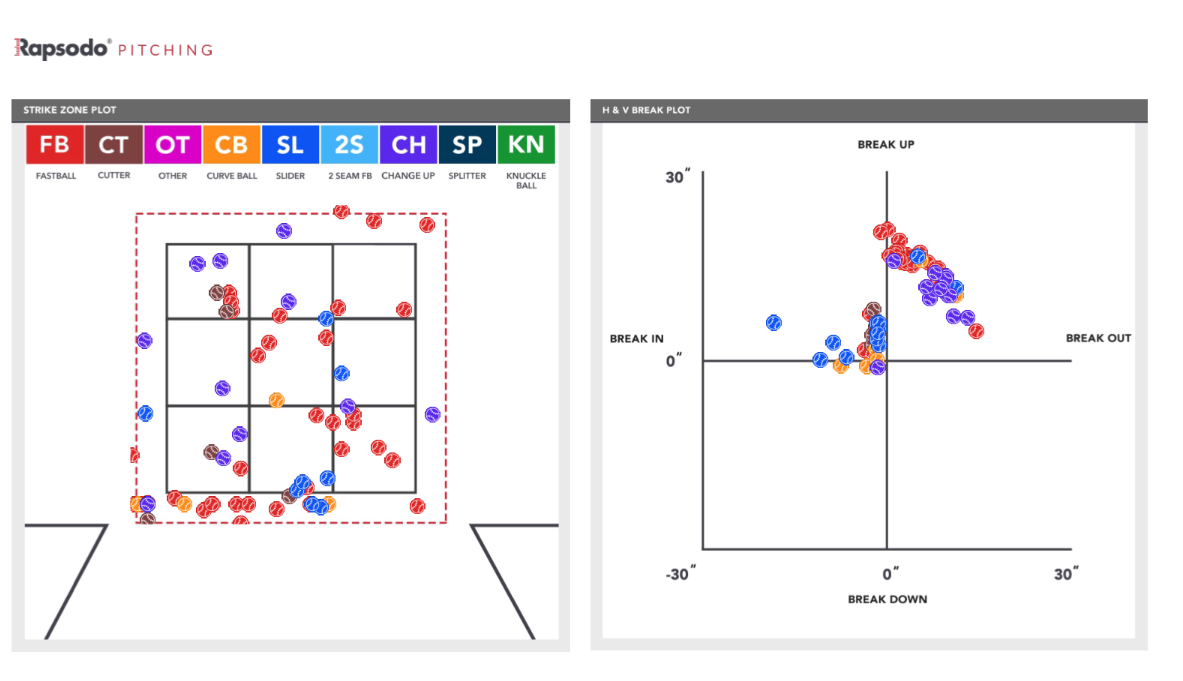

Pitch Data - Cutter - RHP

This small sample size of information is from one short bullpen that shows what is being done with the Cutter. Without this immediate feedback, pitch design becomes much more difficult to match the pitcher’s feel along with data. The Cutter shows it is moving on two different planes with little horizontal movement from spin. Two of the biggest factors are finding the consistency with axis and spin efficiency. Several key things can be abstracted from this data to apply to pitchers of all levels. The conversation between coach and player becomes much more supported by information rather than guessing. Trial and error is ultimately the best route to designing a pitch. If all we are relying on is the naked eye and video, then our rate of success will suffer.

Rapsodo can be used for all ages and skill levels, but should be a priority when working with higher level athletes who are wanting to maximize pitch efficiency. Movement being one of the key factors in pitch ability, you can get a full breakdown of your pitch arsenal in each bullpen.

Image 3

Data Usage

Now, how do we use the data? Rapsodo does a great job of supplying data. But the data means nothing without considering all factors. Pitchers generate spin and movement thanks to several variables such as delivery mechanics, slot, intent, grip, pressure distribution among fingers, etc. Just because Cy Young winners produce “x” type of spin rate does not mean you should aim to match. Numbers are different and unique to each pitcher. Your individualized skill set can be maximized in a completely different way than your peers.

For example, we know that a high spin rate fastball should be used in the top of the strike zone. It fights through gravity better which can is maximized at top of zone (Magnus Force). A low spin fastball should be kept down in the zone as gravity will drive that pitch down and produce more ground balls. With breaking balls, a heavy spin curveball with high efficiency can create heavy tilt and depth. A high spin, low efficiency (below 60%) will have less vertical break but could produce more horizontal movement depending on the axis. A slider from a low ¾ slot with low spin and efficiency will feature more depth from the gyrospin which can produce a high swing and miss rate. A high ¾ slot slider with heavy spin and low efficiency can produce the same result despite different grip, slot, and axis.

Point is, don’t aim for a “goal” on spin rate, axis, or efficiency. Collect data and analyze what is best for your delivery, grip, slot, spin, and tunnelling off of your other pitches.

"Every pitcher is an artist."

How you create your final product can be done in many ways with success. The goal needs to be that it is a repeatable, natural delivery with confidence to maximize soft contact or swing and misses.

Digesting Current MLB Data

With all of the data collection in the MLB these days, we can start to digest the importance of velocity, spin rate, movement, and the results they produce. Data shows that there are several outliers and differences between results and spin rates.

"We know that there is not one single way to develop more spin rate (legally), but there are ways to maximize pitch success within a pitcher’s current capabilities with spinning the baseball."

MLB pitchers feature different spin rates despite great results:

Yu Darvish - Fastball (4-seam) - 2564avg RPM

Gerrit Cole - Fastball (4-seam) - 2450avg RPM

Lance McCullers Jr - Fastball (4-seam) - 2301avg RPM

Bartolo Colon - Fastball (2-seam) - 2085avg RPM

Marcus Stroman - Fastball (2-seam) - 2245avg RPM

Justin Verlander - Curveball - 2803avg RPM

Clayton Kershaw - Curveball - 2364avg RPM

Charlie Morton - Curveball - 2835avg RPM

Sonny Gray - Curveball - 2890avg RPM

Madison Bumgarner - Curveball - 2356avg RPM

Seth Lugo - Curveball - 3337avg RPM

Andrew Miller - Slider - 2625avg RPM

Chris Sale - Slider - 2395avg RPM

Luis Severino - Slider - 2687 avg RPM

Carlos Martinez - Slider - 2185avg RPM

Max Scherzer - Change-Up - 1511avg RPM

Marco Estrada - Change-Up - 2026avg RPM

Johnny Cueto - Change-Up - 1520avg RPM

Kyle Hendricks - Sinker - 1932avg RPM

Jake Arrieta - Sinker - 2259avg RPM

Blake Treinen - Sinker - 2385avg RPM

Jordan Hicks - Sinker - 1985avg RPM

The average spin rate for a fastball in 2019 was 2300rpm for RHP and 2250 for LHP in the MLB.

Source: BaseballSavant

These examples show different spin rates that accomplish the same goal. The efficiency, axis, and slot are what is most important and make the biggest impact on the pitch movement. It’s easy to say that maximizing spin rate can better a pitch. When discussing breaking balls, that could be true when predicting the ceiling of a pitch. But to keep it simple, the goal is to manipulate the baseball with spin and movement. How you accomplish that can vary from subject to subject.

More spin data from 2019 MLB:

2S - 2150-2250rpm

CH - 1700-1800rpm

CB - 2500-2600

Cutter - 2350-2450

SL - 2500-2600

Splitter - 1400-1500

Here is a great link for Rapsodo breakdown for MLB spin averages and understanding the readings - https://rapsodo.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/MLB-PitchingGuide.pdf

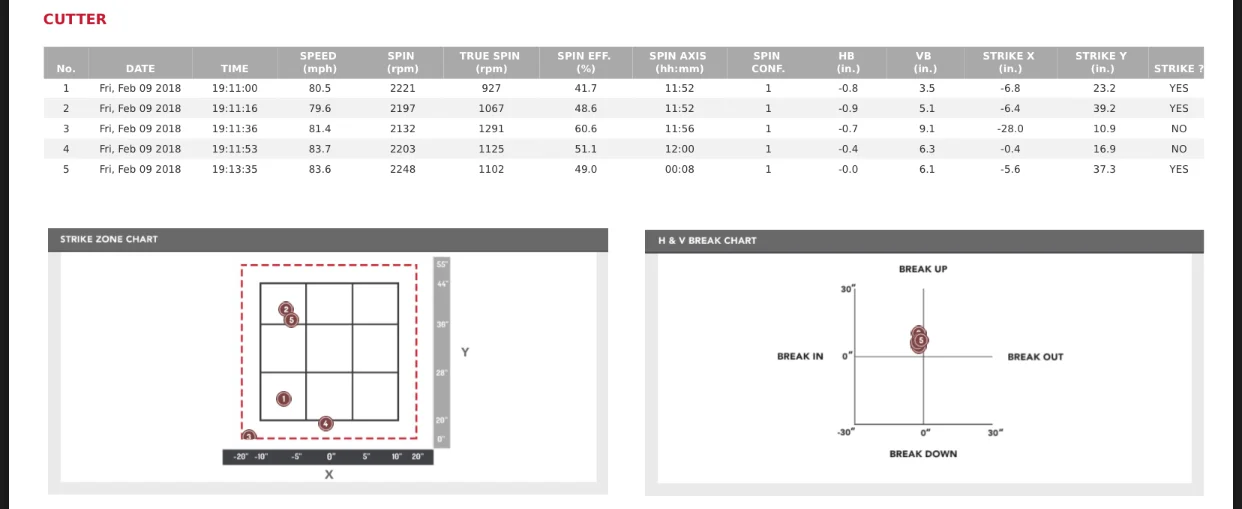

Image 4 (via @mike_petriello on Twitter)

Image above (Image 4) shows that an increased spin rate and velocity can correlate to a higher swinging strike percentage.

Yes, higher fastball velocity leads to more swinging strikes. Image 4 shows data proving that higher spin rates combined with velocity usually equal more swinging strikes as well. Velocity and spin rate are also somewhat correlated. Typically a spin rate will climb with the velocity of the pitcher. Average RPM’s vary at all age levels along with velocity.

With the MLB average being 2264 in 2016 on the 4-seam fastball, this provides a general baseline for how pitchers should attempt to control the zone. High spin rate fastballs should be utilized in the top of the strike zone. Low spin rate fastballs should be utilized in the bottom of the strike zone. Those aren’t absolutes, but in general it provides a common approach that leads to weak contact. Typically, identifying a low spin rate on a 4-seam fastball leads to designing a 2-seam fastball to utilize less true spin and creating even more kill on the vertical break.

Bauer Units

Driveline Baseball posted a Blog in March of 2017 about Bauer Units.

Bauer Units = Spin Rate (RPM) / Velocity (MPH)

This equation provides coaches of all levels easier ways to compare data whether you are a big leaguer or a 14u pitcher. The MLB average was 23.9 Bauer Units. For example, a 72mph fastball at 1750RPM would be 24.3 Bauer Units (Driveline Baseball). When assessing younger athletes or lesser velocities, the Bauer Units formula is a great tool to truly assess where a pitcher stands in comparison to others. This clears up a lot of misunderstandings when working with mid-80’s HS/College pitchers with spin rates around 2,000. A pitcher throwing 84mph at 2100 will have 25 Bauer Units. This information and formula is very important when using Rapsodo for younger pitchers.

Design It

Once you have your pitch profiles, it is time to see what needs maximized while staying within your natural abilities. Here are some measurables for spin efficiency and spin rate to try to combine:

How do you design it? Knowing your spin and axis is step number one. Once you know, it becomes a trial and error process. Adjusting grips, wrist angle, pressure on fingers, and thumb placement are just a few to mention. Each pitcher has different hand and finger size. It takes time and a lot of repetitions. Pitchers must be able to “feel” release and the adjustments on the spin when learning how repeat a pitch. Inconsistent data on Rapsodo is very common when trialing a new grip or pitch. An inconsistent pitch in a bullpen setting is a set up for failure in game when it comes to pitch execution.

There are several ways to drive pitchers towards feeling differences in grip, pressure and release. Making too much of a change one way or another will make it very difficult to find a comfort zone for the pitcher.

Know your data? As mentioned before, this alone is critical to understanding where and how you should be using your arsenal. If you are a high RPM or Bauer Units 4-seam Fastball pitcher, you should be working up in the zone. If you are in the “average” category, you should trial with some adjustments in grip, pressure, and assess your 2-seam spin rates. Below average spin rate, you should be working in the bottom of the zone.

"Most pitchers have never been told to work up in the zone due to the misunderstanding of pounding the knees having a correlation to success. "

Few tips:

If want to throw a harder, higher spin rate off-speed pitch, turn it late and hard. Resisting early hand torque or “fall off” can create a higher velocity and/or spin rate. To keep coaching it simple, think fastball longer before breaking it.

Move your fingers closer together on 4-seam and 2-seam. Several pitchers create a cut action on the baseball as fingers being setup wider on the baseball allows middle finger to pull the side of baseball.

Try pressuring different fingers. Emphasize the middle finger more on a slider than a cutter. Emphasize the pointer finger more on 2-seam and sinkers.

Move the thumb! The thumb does a lot to affect spin. Notice different movements and spins on change-ups, sliders, cutters, 2-seam, 4-seam when tucking the thumb.

Collect video! Must match what you see with what you feel. Slow-motion video of behind the throwing hand will allow you to see what you may or not feel causing the results of the pitch spin and movement.

Be open to suggestions. Not one way works for just one guy. Don’t give up on a new grip or pitch just because you fail the first few reps.

These are just a few staples in developing a new pitch with or without a pitch tracking device. When using a Rapsodo in the bullpen, you can get immediate feedback whether or not moving grips or pressure changed anything with the pitch result.

Peyton Gray creates about 13-15in less vertical break on change-up compared to his fastball by tilting the axis and killing spin.

One of the biggest successes that I’ve personally had with teaching new grips and pitches is the change-up. Pitcher’s want to slow their arm action to ensure lower velocity than fastball. The change-up grip should be something that can be thrown with intent and comfort. The grip and axis will do the work while the delivery and the arm action should think fastball. The goal is to create a lower axis (2:30-3:00 for RHP) that produces lower efficiency than the fastball. This will kill velocity, create depth, and horizontal break. Typcially, this means a true spin of about 500-800 less than the pitcher’s fastball. Grips vary between pitcher’s mechanics and arm slot, but a common cue I personally use is throwing the the thumb and middle finger through the catcher’s mitt. This can motivate the pitcher to create later pronation and enhance intent. Again, this is just one example but have found success with pitcher’s at different levels.

Rep It

Designing and gaining feel for a new pitch is a love/hate relationship. It can take several bullpens before even getting a feel for the new grip or hand positioning.

Goal number one is to get comfortable with it just throwing with a catcher. This can take a while. Recommendation, add it more to your catch play when prior to bullpen. Step two, have a hitter stand in provide feedback. Step three, live at bats with data collection and video analysis to see the translation from bullpen setting to live. It is common for pitch data to change from the bullpen setting to live ABs due to adrenaline and intent.

Collecting that feedback along with batter results can provide very important information that shows the true impact of the pitch adjustment. Now, go back to the lab and see how results transferred over to live. If data wasn’t consistent, get back to work in a controlled bullpen setting.

Summary

Before getting into much change with pitch design, a personal suggestion is to tell the pitcher he has to strike out an elite hitter with his best stuff. Now, collect video and watch. Get a feel for the pitcher does when just trying to produce a filthy pitch without more external cueing. Go to work from there once you have data from Rapsodo and slow-motion video of delivery, grip, and hand positioning. Take Bauer Units, spin axis, movement, and success rates into consideration before breaking down a current pitch.

Having technology such as Rapsodo or Trackman and high-speed video cameras can separate your pitch development from the competition. The ability to digest the data and make necessary adjustments without over-coaching it is an art that is often misunderstood. By all means, pitches have been designed for well over a 100 years now but the ability to do so with immediate feedback outside of the “eye test” can expedite the process very quickly and efficiently.

Throughout a pitcher’s development, pitch design always remains key piece. Understanding the information on spin rates, movements it can cause, and how to utilize in your pitch sequencing are all important variables. Proper coaching and use of the data can separate pitchers from their peers.